Effect on feed intake and growth of depriving rabbits access to caecotropes

Chiv Phiny and Lampheuy Kaensombath*

Center for Livestock and Agriculture Development

CelAgrid-UTA, Cambodia, Phnom Penh

phiny_kh@yahoo.com

*Faculty of Agriculture, National University of Laos (NUOL)

Vientiane, Laos

Abstract

Twelve young rabbits with average live weight of 713 g were allocated to four treatments in a 2*2 factorial arrangement with three replications in a randomized block design. The treatments were water spinach with: access to caecotropes; plus rice bran and with access to caecotropes; without access to caecotropes (a plastic collar around the neck to prevent access to the anus); plus rice bran without access to caecotropes. .

The water spinach offered had a a similar (about 50% of each) proportion of leaves and stems, while the refusals were much higher in stems, reflecting selection for the leaf component in the foliage consumed. Daily DM intakes of water spinach and rice bran were not affected by the rabbits having access or not to caecotropes. Supplementation with rice bran led to decreased intake of water spinach but an increase in total DM intake. The growth rate was reduced by almost 50% when the rabbits were denied access to their caecotropes. There were no apparent advantages in supplementing the water spinach with rice bran. Feed conversion rates tended to be better when the rabbits had access to caecotropes. Caecotropes had lower contents of DM and crude fibre but almost 50% higher content of crude protein.

It is concluded that fresh water spinach can be given as the sole feed for growing rabbits; that there appears to be no advantage in supplementing it with rice bran; and that the practice of caecotrophy confers important nutritional benefits.

Key words: Caecotrophy, growth, feed intake, rabbits, water spinach.

Introduction

In tropical countries such as Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia, most farmers keep livestock for their main source of income. Rabbit production is a relatively new development in the region, which nevertheless promises to play an increasing role in view of the economic risks posed by the spread of bird flu (Benigno et al 2005). . In industrial countries, diets for rabbits are usually made from cereal grains and alfalfa prepared as pellets (Lebas et al 1997); however, in developing countries such feeds are expensive and there is a need to develop alternatives which make greater use of local resources. There are some recent reports concerning the use of tropical foliage as a supplementary source of protein for this specie (Akinfala et al 2003; Sarwatt et al 2003). However, more important developments are those described by Hongthong Phimmasan et al (2004) and Samkol et al (2006) in which water spinach - a local forage source - was used as the sole diet of growing rabbits, supporting growth rates of 15 to 20 g/day.

Water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) is a vegetable that is consumed by people and animals; it has a short growth period, is resistant to common insect pests and can be cultivated either in dry or flooded soils. Moreover, it has been found that water spinach has a high potential to convert nitrogen from biodigester effluent into edible biomass with high protein content (Kean Sophea and Preston 2001). Water spinach has the potential to play an important role for farmers and animasl in rural areas, because it is easy to plant and has a very high yield of biomass, which is rich in protein. The crude protein content in the leaves and stems can be as high as 32 and 18 % in dry basis, respectively (Ly Thi Luyen and Preston 2004).

McNitt et al (1996) fed rabbits with different feed sources, which were either balanced concentrate feeds, or green and dry forage, and measured the nutrients in the faeces and caecotropes. The major difference in composition was in the DM content (lower in caecotropes) and crude protein (much higher in the caecotropes) (Proto 1980).

The following experiment was designed to study the effects on growth and feed conversion of depriving rabbits of access to the caecotropes, when they were fed a diet based on fresh water spinach.

Hypothesis

The hypothesis to be tested was that rabbits would have a lower feed intake and lower growth rate when they were prevented from consuming the caecotropes, and that growth rate would be improved when when the basal diet of water spinach was supplemented with rice bran.

Materials and methods

Location

This experiment was conducted in the Livestock Research Center, Nam Xuang, over the period 17 September to 17 October 2005.

Experimental design and treatments

Twelve young rabbits with average live weight of 713g were allocated to four treatments in a 2*2 factorial arrangement with three replications in a randomized block design (see Table1). The rabbits were confined in individual cages constructed from wood and iron net. The treatments were:

-

Y-WS : Water spinach with access to caecotropes

-

Y-WSRB : Water spinach and rice bran separately with access to caecotropes

-

N-WS: Water spinach without access to caecotropes

-

N-WSRB : Water spinach and rice bran separately without access to caecotropes

|

Table 1: Layout of experiment |

||||||

|

Block |

I |

II |

III |

|||

|

Cages |

Y-WS |

N-WS |

Y-WSRB |

Y-WS |

N-WS |

N-WSRB |

|

N-WSRB |

Y-WSRB |

N-WSRB |

N-WS |

Y-WS |

Y-WSRB |

|

Feeding and management

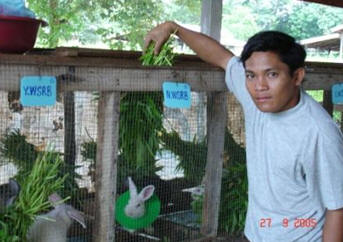

Water spinach was harvested from plots in the research centre, cutting the stems about 1 cm above soil level, in order to facilitate the re-growth. The leaves combined with the stems of the water spinach were hung as a bunch at the side of the cage (Photo 1). The rice bran was bought from neighbouring farmers. It was put in a small feeder, made from wood and was tied to the individual cage wall.

Photo 1: Rabbits with or without access to caecotropes (by fitting a plastic collar around the neck)

The two kind of feed were offered to the rabbits two times a day, beginning in the morning at 6:00 am. Observations was made, mainly at midday (12:00 m) and in the evening (4:30 pm), in order to ensure the permanent availability of water spinach and rice bran. The proportions of leaves and stems (fresh basis) in the water spinach were recorded daily in the foliage that was offered and refused. Water was not provided.

Animal housing

The cages were made from wood and iron net with dimensions of length 0.5m, width 0.5m and height 0.7m. There were holes in the cage floor of approximately 1cm2 (See Photo1).

Photo 2: Rabbits in the individual cages

Measurements

Faeces were collected and weighed daily. About 10% of the daily amount was kept frozen in plastic bags until analysis at the end of every four days. Water spinach offered and refused was recorded every day, and separated into leaves and stems. Samples of each plant component, offered and refused, and fresh faeces were analysed for DM, N and crude fibre. Analyses were done on fresh material after grinding in a coffee grinder.

The rabbits were weighed at 5 day intervals before offering fresh feed in the morning.

Chemical analyses

Chemical analyses of the diets, refusals, faeces and caecotropes were undertaken following the methods of AOAC (1990) for ash, N and crude fibre. DM was determined using the micro-wave radiation method of Undersander et al (1993). Water extractable DM and N were determined by the methods described by Ly and Preston (2001).

Statistical analysis

The data were subjected to analysis of variance using the General Linear Model (GLM) option of the MINITAB software (Release 13.31, 2000). Sources of variation were: blocks, access (or not) to caecotropes, rice bran, interaction caecotropes*rice bran and error.

Results and discussion

Feed characteristics

DM and N contents were higher and crude fibre lower in leaves compared with the stems of the water spinach (Table 2). The low N content and high fibre of the rice bran probably reflected contamination with rice husks. The water spinach offered had a a similar proportion of leaves and stems, while the refusals were much higher in stems, reflecting selection for the leaf component in the foliage consumed (Table 3; Figure 1). The degree of selection for leaves was greater when the rabbits had no access to caecotropes as opposed to having access, and when they were supplemented with rice bran.

|

Table 2: Feed characteristics (% in dry basis, except for DM which is on fresh basis) |

||||

|

|

DM |

N*6.25 |

Ash |

Crude fibre |

|

Rice bran |

87.3 |

8.45 |

10.0 |

26.6 |

|

Water spinach |

|

|

|

|

|

Leaves |

12.9 |

24.6 |

11.2 |

14.2 |

|

Stem |

8.43 |

9.91 |

14.4 |

20.3 |

|

Table 3 . Mean values for leaf fraction in water spinach, according to the rabbits having access or not to caecotropes and supplementation with rice bran |

|||||||

|

|

Caecotropes |

Rice bran |

|

||||

|

Leaf fraction (DM basis) |

No |

Yes |

Prob. |

No |

Yes |

Prob |

SEM |

|

Offered |

0.499 |

0.499 |

|

0.499 |

0.499 |

0.499 |

0.0039 |

|

Refused |

0.131 |

0.181 |

0.001 |

0.152 |

0.160 |

0.131 |

0.0086 |

|

Consumed |

0.648 |

0.621 |

0.014 |

0.611 |

0.658 |

0.001 |

0.0078 |

Figure 1: DM intake of water spinach and rice bran of

rabbits with and without access to caecotropes

Feed intake

Daily DM intake of water spinach and rice bran was not affected by the rabbits having access or not to caecotropes (Table 4 and Figure 1). However, supplementation with rice bran led to decreased intake of water spinach but an increase in total DM intake.

|

Table 4. Mean values for DM intake of feeds, according to the rabbits having access or not to caecotropes and supplementation with rice bran |

|||||||

|

|

caecotropes |

Rice bran |

|

||||

|

|

No |

Yes |

Prob. |

No |

Yes |

Prob. |

SEM |

|

Water spinach |

54.9 |

55.3 |

0.74 |

62.6 |

47.7 |

0.001 |

0.91 |

|

Rice bran |

10.2 |

10.7 |

|

0.0 |

20.9 |

|

|

|

Total |

65.1 |

66.1 |

0.53 |

62.6 |

68.6 |

0.001 |

1.1 |

Growth and feed conversion

The growth rate was reduced by almost 50% when the rabbits were denied access to their caecotropes (Table 5 and Figure 2). There were no apparent advantages in supplementing the water spinach with rice bran. Feed conversion rates tended to be better (P=0.02) when the rabbits had access to caecotropes (Table 5).

|

Table 5. Mean values for changes in live weight and in DM feed conversion of rabbits fed water spinach with access or not to caecotropes and supplementation or not with rice bran |

|||||||

|

|

Caecotropes |

|

Rice bran |

|

|

||

|

|

No |

Yes |

Prob |

No |

Yes |

Prob. |

SEM |

|

Live weight, g |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Initial |

877 |

765 |

|

867 |

775 |

|

49 |

|

Final |

1187 |

1323 |

|

1293 |

1217 |

|

44 |

|

Daily gain |

11.1 |

21.4 |

0.001 |

16.3 |

16.2 |

0.94 |

1.04 |

|

DM conversion |

5.53 |

3.86 |

0.2 |

4.93 |

4.46 |

0.4 |

0.82 |

Figure 2: Effect of access or not to caecotropes on the growth rate of rabbits

fed water spinach with or without supplementation with rice bran

Faecal characteristics

There were major differences in the composition of the faeces with increases in DM, N and crude fibre content when the rabbits were deprived of access to their caecotropes (Table 6). Supplementation with rice bran led to increases in DM content and ash content but no effect on crude fibre content.

|

Table 6. Mean values for composition of faeces of rabbits fed water spinach with access or not to caecotropes and supplementation or not with rice bran |

|||||||

|

|

Caecotropes |

Rice bran |

|

||||

|

No |

Yes |

Prob. |

No |

Yes |

Prob. |

SEM |

|

|

DM, % |

52.8 |

44.1 |

0.001 |

43.5 |

53.4 |

0.001 |

0.72 |

|

As % of DM |

|||||||

|

N |

3.33 |

2.84 |

0.001 |

3.51 |

2.67 |

0.001 |

0.06 |

|

Crude fibre |

35.6 |

33.2 |

0.001 |

34.0 |

34.9 |

0.31 |

0.62 |

|

Ash |

14.1 |

13.8 |

0.19 |

13.4 |

14.6 |

0.001 |

0.16 |

A comparison of composition of caecotropes and faeces was made using the data for rabbits denied access to the caecotropes (Table 7 and Figure 3). Caecotropes had lower contents of DM and crude fibre but almost 50% higher content of crude protein. These findings are similar to those reported by Proto (1980).

|

Table 7. Composition of caecotropes and faeces from rabbits not allowed to consume the caecotropes (DM is % on fresh basis; the rest as % of DM) |

||||

|

|

Faeces |

Caecotropes |

SEM |

Prob. |

|

DM |

53.2 |

27.6 |

0.671 |

0.001 |

|

Crude fibre |

35.2 |

20.1 |

0.370 |

0.001 |

|

Crude protein |

21.0 |

27.9 |

0.523 |

0.001 |

|

Ash |

14.2 |

13.1 |

0.135 |

0.001 |

|

N in DM |

3.36 |

4.47 |

0.084 |

0.001 |

Conclusions

-

Depriving growing rabbits of access to caecotropes did not affect DM intake; led to 50% poorer growth rate and feed conversion; and stimulated slightly the selection of leaf of water spinach rather than stem

-

Supplementing fresh water spinach with rice bran appeared to confer no benefits in terms of rate of growth and feed conversion in growing rabbits

-

The caecotropes from rabbits fed water spinach, with or without rice bran, were much richer in nutrients than the faeces.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their appreciation to the MEKARN

program funded by SIDA-SAREC project for providing the opportunity and budget to

carry out the project. Thanks are also given to Mr. Chhay Ty and

the Director of the Livestock Research Center including staff members, for

their help in facilitating the execution of the experiment.

References

Akinfala E O, Matanmi O and Aderibigbe A O 2003. Preliminary studies on the response of weaned rabbits to whole cassava plant meal basal diets in the humid tropics. Livestock Research for Rural Development 15(4): http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd154/akin154.htm

AOAC 1990. Official methods of analysis. Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 15th edition. Arlington pp1290

Benigno C, Wagner H and Wantanee Kalpravidh 2005 Outbreak of avian influenza in Asia. Proceedings AHAT-BSAS Conference (Editors: P Rawlinson and M Wanapat) Khon Kaen University, November 15 to 18, 2005

Hongthong Phimmmasan, Siton Kongvongxay, Chhay Ty and Preston T R 2004 Water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) and Stylo 184 (Stylosanthesguianensis CIAT 184) as basal diets for growing rabbits. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Vol. 16, Art. #34.Retrieved , from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd16/5/hong16034.htm

Kean Sophea and Preston T R 2001 Comparison of biodigester effluent and urea as fertilizer for water spinach vegetable. Livestock Research for Rural Development (13) 6; http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd13/6/Kean136.htm

Lebas F, Coudert P, Rochambeau H de and Thebault R G 1997 Rabbit Husbandry, Health and Production. FAO Animal Production and Health Series No. 21.

Ly Thi Luyen and Preston T R 2004 Effect of level of urea fertilizer on biomass production of water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) grown in soil and in water. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Vol. 16, Art. #81. Retrieved , from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd16/10/luye16081.htm

Ly J and Preston T R 2001. In vitro estimates of nitrogen digestibility for pigs and water-soluble nitrogen are correlated in tropical forages feeds. Livestock Research for Rural Development 13(11): http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd13/1/ly131.htm

McNitt J I, Patton N M, Lukefahr S D and Cheeke P R 1996 . Rabbit production ( 7th edition). Interstate Publishers Inc. Danville, Illinois. Pp 144-278.

Pok Samkol, Preston T R and Ly J 2006 Effect of increasing offer level of water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) on intake, growth and digestibility coefficients of rabbits. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 18, Article #25. Retrieved , from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd18/2/samk18025.htm

Proto V 1980 Alimentazione del coniglio da carne. Coniglicoltura, 17(7): 17-32.

Sarawatt S V, Laswai G H and Ubwe R 2003: Evulation of the potential of Trichanthera gigantean as a source of nutrients for rabbits diets under small holder production system in Tanzania. Livestock Research for rural Development(15) 11 Retrieveed September 21, 2003, from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd15/11/sarw1511.htm

Undersander D, Mertens D R and Lewis B A 1993.Forage analysis procedures. National Forage Testing Association. Omahapp 154