Growth performance of pigs fed water spinach or water spinach

mixed with mulberry leaves, as protein sources in basal diets of

cassava root meal plus rice bran or sugar palm syrup plus broken

rice

Chiv Phiny, B Ogle*, T R Preston ** and Khieu Borin

Centre for Livestock and Agriculture

Development,

PO. Box 2423, Phnom Penh 3, Cambodia

chphiny@celagrid.org

* Department of Animal Nutrition and Management,

SLU

** TOSOLY, UTA-Colombia,

AA#48, Socorro, Santander, Colombia

Abstract

The aim of the study was to determine the effect on growth

performance of pigs of a mixture of mulberry leaves with water

spinach compared with water spinach alone as protein supplements to

energy sources with different levels of fibre, derived from cassava

root meal plus rice bran or sugar palm syrup plus broken rice.

Sixteen female crossbred pigs (Large White X Local breed) of

average live weight 20kg were allocated into 4 treatments in a 2*2

factorial arrangement with 4 replications. The factors were the

energy source (cassava root meal plus rice bran [CRRB] or sugar

palm syrup plus broken rice [SPBR]) and the protein source (water

spinach [W] or a 50:50 mixture of water spinach and mulberry leaves

[WM]).

Key words: Diuretic effect, energy sources, feed conversion,

Introduction

Due to the competing demand for cereal grains between the expanding human and livestock population in the world, there is an urgent need for research to develop local natural feed resources for both ruminant and monogastric animals, especially for pigs.

Water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) is a water and marsh plant with creeping and hollow, water filled stems and shiny green leaves. It is a cash crop cultivated by smallholder farmers within the existing farming systems in Cambodia. It can grow very well when fertilized with the effluent from biodigesters charged with pig manure (Kean Sophea and Preston 2001). Fresh biomass yields of up to 24 tonnes/ha were achieved in a growth period of 30 days from the sowing time of seed. In Cambodia and throughout Southeast Asia, water spinach has been cultivated for human food, and is also fed to pigs and other animals. The fresh stem and leaves of water spinach have a crude protein content of between 20 and 30% in DM (Le Thi Men et al 2000) and ash concentrations of around 12% in DM (Göhl 1981). According to Prak Kea et al (2003) and Ly et al (2002), water spinach is a protein-rich forage which can replace part, or the whole of the fish or soybean meal. Chhay Ty and Preston (2006) found that a 50:50 mixture of cassava leaves and water spinach supported much higher growth rates than when the cassava leaves was the only source of supplementary protein.

The most important use of mulberry (Morus

alba) foliage is to feed silk worms (Tingzing et al 1988).

However, active research on use of mulberry foliage for animal

feeding is currently taking place in Japan, India, Colombia and

Cuba (Sanchez 1999). Mulberry leaves have been fed successfully to

ruminants in Vietnam. Nguyen Xuan Ba et al (2005) reported that

growth rates of goats increased with increasing proportions of

ensiled mulberry leaves replacing grass, and Vu Chi Cuong et al

(2005) showed that for cattle, fresh mulberry leaves had the same

protein value as cottonseed meal.

Less is known about the use of mulberry leaves as a protein supplement for pigs. In a preliminary study in Cambodia, Chiv Phiny et al (2003) found that pigs showed a slight preference for fresh versus sun-dried leaves and that DM digestibility increased with increasing proportions of mulberry leaves in the diet. Chhay Ty et al (2007 unpublished data) reported that the apparent digestibility of dry matter was higher in fresh mulberry leaves as compared with a mixture of mulberry and sweet potato vines. In a growth performance experiment with pigs, González et al (2006) reported that mulberry leaf meal (MLM) could be fed at up to 18% of the diet DM, replacing conventional protein sources, without affecting growth performance in pigs given basal diets of maize meal or sugar cane juice.

In Cambodia, CelAgrid is developing alternative feed resources

for livestock feeding, particularly for pigs, using mulberry leaves

which are considered to be an appropriate supplement, because of

the high protein content of 18 to 25% in DM (Chiv Phiny et al

2006).

A characteristic of whole water spinach and mulberry leaves as vegetative sources of protein is the low energy density because of the relatively high cell wall content. Thus, the forage could be a factor limiting intakes by pigs. One way to correct this problem is to combine the leaves with energy sources that are low in fibre. Cassava root meal, sugar palm syrup, palm oil, sugar cane juice and broken rice are energy sources with low or zero content of fibre and protein. Thus they could be appropriate basal feeds for combining with protein-rich foliage in water spinach and mulberry leaves. In Cambodia, sugar palm syrup was used successfully as the energy source for pigs complemented with boiled whole soya beans (Khieu Borin and Preston 1995).

Chhay Ty and Preston, (2005) reported that there appeared to be synergistic positive effects on growth performance of pigs when water spinach was combined with fresh cassava leaves. Chittavong Malavanh and Preston (2006) indicated that water spinach and sweet potato leaves appeared to have the same nutritive value when used to supplement a basal diet of cassava root meal and rice bran for growing pigs.

The aim of the present trial was to determine if

there would be advantages from combining water spinach with

mulberry leaves as compared with water spinach as the only protein

supplement, in diets with different levels of fibre derived from

cassava root meal plus rice bran or sugar palm syrup plus broken

rice.

Materials and methods

Location and climate

The experiment was carried out from November 15, 2006 to February 15, 2007 in the Ecological farm of the Center for Livestock and Agriculture Development, (CelAgrid- Cambodia), located in Prah Theat village, Rolous commune, Kandal Steung district, Kandal Province, Phnom Penh City, Cambodia. The ambient temperature during the trial was about 35oC in the middle of the day (12.00h).

Experimental design and treatments

A total of 16 crossbred female pigs with an average live weight of 20 kg, were allocated to 4 treatments in a 2*2 factorial arrangement with 4 replications in a Randomized Block Design. The pigs were allocated to the blocks in order of live weight and to treatments within blocks at random. The experimental layout is in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Layout of experiment |

||||||||

|

|

I (LW 16.9 kg) |

II (LW 18.5kg) |

III (LW 19.7kg) |

IV (LW 22.0kg) |

||||

|

Block |

WCRRB |

WMSPBR |

WMCRRB |

WCRRB |

WSPBR |

WCRRB |

WMSPBR |

WMCRRB |

|

Pens |

WMCRRB |

WSPBR |

WMSPBR |

WSPBR |

WMSPBR |

WMCRRB |

WCRRB |

WSPBR |

The two factors were:

-

Energy source: Cassava root meal plus rice bran or sugar palm syrup plus broken rice

-

Protein source: Water spinach or a 50:50 mixture of water spinach and mulberry leaves

The individual treatments were:

-

WCRRB : Water spinach with cassava root meal plus rice bran

-

WSPBR : Water spinach with sugar palm syrup plus broken rice

-

WMCRRB: Mixture of water spinach and mulberry leaves (50: 50 DM basis) with cassava root meal plus rice bran

-

WMSPBR : Mixture of water spinach and mulberry leaves (50: 50 DM basis) with sugar palm syrup plus broken rice

Experimental feeds

Water spinach was purchased daily in the local market. Cassava root meal, rice bran, broken rice and sugar palm syrup were bought every week, also in the local market. The mulberry leaves were harvested from plots in CelAgrid. Water spinach and mulberry leaves were chopped into small pieces of about 0.5-1cm. The foliages and the energy component were fed to appetite but in separate troughs so as to record intakes separately of the energy and protein components (the quantities offered were adjusted to have minimum residues). In each case the energy sources and the foliages were each mixed thoroughly by hand before putting them in the separate feed troughs. A premix of minerals, vitamins and salt was added daily to the foliage component. The pigs were fed three times per day, at 0700h, 12.00h and 16.00h. Water was permanently supplied through automatic drinking nipples. The chemical composition of the ingredients is shown in Table 2.

|

Table 2. Chemical characteristics of the ingredients of the diets |

||||

|

Ingredients |

DM % |

As % of DM |

||

|

CP |

CF |

Ash |

||

|

Cassava root meal |

87.5 |

2.5 |

7.0 |

2.38 |

|

Rice bran |

91.0 |

13.0 |

11.9 |

10.2 |

|

Sugar palm syrup |

81.9 |

0.24 |

nd |

nd |

|

Broken rice |

87.0 |

9.4 |

2.0 |

0.63 |

|

Water spinach |

9.10 |

25.7 |

22.8 |

16.2 |

|

Mulberry leaves |

31.3 |

22.1 |

16.0 |

22.2 |

|

Premix / salt |

98.0 |

nd |

nd |

nd |

|

nd= not determined |

||||

Animals and housing

A total of sixteen female pigs were housed in individual pens with concrete floors and brick walls. The pens were 1.2 m wide, 1.6 m in length and 1 m in height (Photo 1). In each experimental pen there was one drinking nipple and two feed troughs, in order to separate the ingredients of the diets; vegetative protein sources in one trough and energy sources in the other. The pens were in an open shed covered by a roof made from wood, bamboo and thatch (Photo 2). The pigs were vaccinated against common infectious diseases, and de-wormed and then adapted to the diets and the pens for 15 days before starting the experiment.

|

|

|

|

Photo 1. Pigs in individual pens, each with two feeders and one

drinking nipple |

Photo 2. Individual pig pens made from concrete, wood and

bamboo, with divisions |

Data collection

The animals were weighed in the morning before feeding, at the beginning of the trial and every 10 days thereafter. Feed offers and refusals were collected and weighed every day, and samples kept frozen at -200C in plastic bags until analysis. At the end of each 10 day period, samples of feed refused and offered were mixed thoroughly by hand and homogenized in a coffee grinder prior to analysis.

Chemical analysis

Chemical analysis of the feed ingredients, diets and refusals were undertaken following the methods of AOAC, (1990) for ash, N, and crude fibre. The DM content was determined using the microwave method of Undersander et al (1993). All the analyses were conducted in duplicate. Amino acid analyses were carried out by AnalCen Nordic AB (Sweden).

Statistical analysis

The data for feed intake, feed conversion and growth rate were

compared by using the general linear model (GLM) option in the

Minitab ANOVA software release 13.31 (2000). The sources of

variation were: blocks, protein source, energy source, interaction

of protein* energy and error.

Results

During the trial, all but one of the pigs were in good health with no symptoms of discomfort from the consumption of the experimental diets. One pig on treatment WSPBR did not adapt to the diet and lost live weight during the 30-90 day period of the experiment. In the statistical analysis a missing value was fitted for this animal.

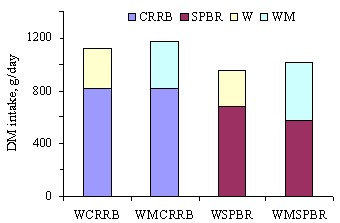

The factorial analysis showed that there were no significant interactions between energy and protein sources for all the measured traits. The results for intakes of energy sources and protein sources are presented in Table 3 and Figure 1, for individual treatments; those for growth rate and conversion are presented as main effects (Table 5).

|

|

|

|

Figure 1. Intakes of dietary ingredients |

Feed intake

Intakes of DM and crude protein were higher for the CRRB compared with the SPBR diets (P<0.001), and were higher when mulberry leaves were mixed with the water spinach compared with water spinach as the only forage (P<0.001) (Table 4; Figure 1).

|

Table 4. Mean intakes of dry matter (DM) and crude protein (CP) (main effects), 0 to 90 days |

|||||||

|

|

CRRB |

SPBR |

P-value |

W |

WM |

P-value |

SEM |

|

DM, g/day |

1149 |

984 |

0.001 |

1036 |

1097 |

0.001 |

11.3 |

|

DM, g/kg LW |

41.5 |

36.1 |

0.001 |

39.1 |

38.5 |

0.113 |

0.23 |

|

CP, g/day |

171 |

132 |

0.001 |

147 |

156 |

0.001 |

1.66 |

|

CP, % of DM |

14.9 |

13.4 |

0.001 |

14.2 |

14.2 |

0.72 |

0.08 |

Growth and feed conversion

There were no differences in final live weight and live weight gain due to the energy source (Table 5). However, overall feed conversion was significantly better (P=0.02) for pigs on the diets with sugar palm syrup and broken rice compared with cassava root meal and rice bran. There were indications that final live weight, live weight gain and feed conversion were numerically improved (P=0.27, P=0.22 and P=0.22) when mulberry leaves were mixed with the water spinach.

|

Table 5. Mean values for main effects on growth rate and feed conversion of pigs fed: cassava root |

|||||||||

|

|

CRRB |

SPBR |

P-value |

W |

WM |

P-value |

SEM |

||

|

Live weight, kg |

|||||||||

|

Initial |

21.8 |

20.3 |

|

20.5 |

21.5 |

0.16 |

|

||

|

30 days |

25.7 |

24.2 |

0.31 |

23.9 |

25.9 |

0.18 |

0.96 |

||

|

60 days |

31.1 |

30.9 |

0.90 |

29.5 |

32.5 |

0.17 |

1.42 |

||

|

Final |

39.2 |

39.5 |

0.90 |

37.5 |

41.2 |

0.27 |

2.24 |

||

|

Live weight gain, g/day |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

0 - 30 days |

207 |

196 |

0.77 |

178 |

225 |

0.24 |

26.1 |

||

|

30 – 60 days |

183 |

224 |

0.24 |

186 |

222 |

0.30 |

23.2 |

||

|

60 – 90 days |

264 |

280 |

0.72 |

261 |

282 |

0.64 |

32.7 |

||

|

0 - 90 days |

209 |

231 |

0.52 |

198 |

242 |

0.22 |

23.1 |

||

|

FCR, kg/kg of body weight |

|

||||||||

|

0 - 30 days |

4.58 |

4.34 |

0.68 |

4.91 |

4.01 |

0.15 |

0.40 |

|

|

|

30 – 60 days |

7.05 |

4.55 |

0.04 |

5.97 |

5.63 |

0.74 |

0.72 |

|

|

|

60 – 90 days |

5.21 |

4.02 |

0.03 |

4.54 |

4.68 |

0.77 |

0.33 |

|

|

|

0 - 90 days |

5.63 |

4.28 |

0.02 |

5.24 |

4.67 |

0.22 |

0.30 |

|

|

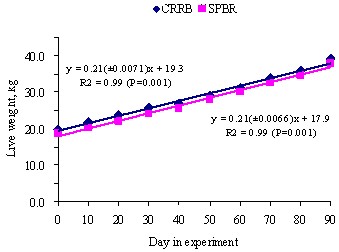

Analysis of the growth curves for the main effects confirmed the absence of differences between energy sources (Figure 2).

|

|

|

|

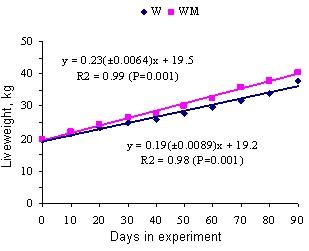

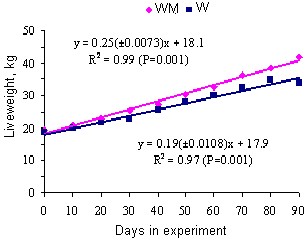

It appeared that growth rates were higher in pigs fed mixtures of mulberry leaves and water spinach compared with water spinach alone (Figures 3 and 4; Table 6).

|

|

|

|

Figure 3. Growth curves of pigs fed cassava root meal and rice

bran supplemented with water spinach [W] or water spinach +

mulberry leaves [WM] |

Figure 4. Growth curves of pigs fed sugar palm syrup and broken rice supplemented with water spinach [W] or water spinach + mulberry leaves [WM] |

The test of the significance of the difference between two slopes is derived from the model:

(b2-b1)/sqrt(s12 + s22)

Where

b1 = regression coefficient of LWG against time for

W

b2 = regression coefficient of LWG against time for

WM

s1 = SE of b1

s2 = SE of b2

Discussion

The better feed conversion on the sugar palm syrup-broken rice diet, compared with cassava root meal and rice bran, can be explained by the lower fibre content of this diet and its higher DM digestibility (Phiny et al 2008). The indications of better growth rates and feed conversion by supplying supplementary protein as mixed foliage of mulberry leaves and water spinach compared with water spinach alone is supported by the significantly higher N retention recorded for the mixed foliage diet in the study on digestibility and N balance (Phiny et al 2008). Mulberry contains higher concentrations of lysine, methionine plus cystine and threonine in the crude protein; however, the ratios of these amino acids as a proportion of the lysine are similar in both feeds and closely resemble the ideal protein (Table 7). It is therefore unlikely that the balance of amino acids was the reason for the superiority of the mulberry-water spinach mixture.

|

Table 7. Major essential AA in the “ideal protein” and in leaves of mulberry and foliage of water spinach |

|||

|

|

Ideal protein (1) |

Water spinach (2) |

Mulberry (2) |

|

g AA/kg N*6.25 |

|

||

|

Lysine |

|

42.7 |

50.6 |

|

Methionine |

13.5 |

16.5 |

|

|

Cystine |

|

10.3 |

12 |

|

Met+Cys |

|

23.8 |

28.6 |

|

Threonine |

|

39.5 |

45.1 |

|

As proportion of lysine = 100 |

|

||

|

Lysine |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Met+Cys |

59 |

56 |

56 |

|

Threonine |

75 |

92 |

89 |

|

(1)Wang and

Fuller 1989 |

|||

There appears to be only one report of a feeding trial to evaluate mulberry leaves for growing pigs (Gonzalez et al 2006). The authors concluded that mulberry leaf meal (levels of 8 and 16% in the diet DM) could replace conventional protein sources in the diets of growing pigs with no loss of performance.

One aspect of the effect of the treatments in this experiment (and in Phiny et al 2008) is the possible superior nutritive value of the mulberry leaves compared with water spinach, and on the other, the potential benefits from reducing the level of water spinach (from an average of 28% in W treatments to about 18% in DM in WM treatments). Chittavong Malavanh and Preston (2006) reported that urine volume and urine N excretion were reduced when sweet potato leaves replaced half of the water spinach in pigs fed a basal diet of rice bran and cassava root meal. We observed a similar effect (Phiny et al 2008) of reduced urine volume and urine N excretion when 50% of the water spinach was replaced by mulberry leaves. Urine volume and urinary N excretion increased in goats when water spinach replaced cassava foliage as the basal diet (Pathoummalangsy Khamparn and Preston 2006) and was higher in goats fed water spinach compared with guinea grass, stylo or cassava foliage (Pheng Buntha and Chhay Ty 2006). Increased urine N excretion and increased urine volume with increasing levels of water spinach in the diet could be caused by the diuretic effect of water spinach, reported in mice by Mamun et al (2003). The dose rate used by these authors was similar, on a metabolic body weight basis, to the levels in the [W] diets in our experiment. The diuretic effect of high levels of water spinach it is assumed would lead to reduced biological value of the protein for N retention and growth, and could explain some of the benefits from replacing water spinach with mulberry leaves in the present study.

Conclusions

-

Intakes of DM and crude protein were higher for CRRB compared with SPBR diets and were increased when mulberry leaves were mixed with the water spinach compared with water spinach as the only forage.

-

Growth rates and feed conversion were numerically improved (P=0.22) when mulberry leaves were mixed with the water spinach compared with water spinach as the only forage.

-

It is suggested that the diuretic effect associated with water spinach could be responsible for the poorer growth performance when it is given at high levels (>28% in DM) in the diet.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thanks the MEKARN project,

financed by Sida/SAREC for supporting this research. Thanks are

given to the staff of CelAgrid for assistance during the entire

experment, especially Mr Oum Sitha, Seng Theara and Seun Bros for

taking care of the feeding and management of the pigs. Thanks to Mr

Chhay Ty and Pek Samnang for helping to analyse the experimental

samples in the laboratary.

References

AOAC 1990 Official Methods of Analysis. Association of

official analytical chemists. 15th edition (K Helrick

editor). Arlington pp1230

Chiv Phiny, Preston T R and Ly J 2003 Mulberry (Morus

alba) leaves as protein source for young pigs fed rice based diet:

Digestibility studies. Livestock Research for Rural Development

(15) 1. http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd15/1/phiny151.htm

Chiv Phiny, Khieu Borin and Chhay Ty 2006 The use of

different levels of effluent from plastic biodigester loaded with

pig manure for mulberry (Morus alba) tree growth. Centre for

livestock and Agriculture Development, CelAgrid-Cambodia. Workshop

on Forages for Pigs and Rabbits. http://www.mekarn.org/proprf/phin.htm

Chittavong Malavanh and Preston T R 2006 Intake and

digestibility by pigs fed different levels of sweet potato leaves

and water spinach as supplements to a mixture of rice bran and

cassava root meal. http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd18/6/mala18086.htm

Chhay Ty and Preston T R 2005 Effect of water spinach and fresh cassava leaves on growth performance of pigs fed a basal diet of broken rice. http://pigtrop. Cirad.fr/en/scientific/alim_LRRD03005_1.htm

Chhay Ty and PrestonT R 2006 Effect of

different ratios of water spinach and fresh cassava leaves on

growth of pigs fed basal diets of broken rice or mixture of rice

bran and cassava root meal. http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd18/4/chha18057.htm

Chhay Ty, Borin K and Chiv Phiny 2007: A note on the effect of fresh mulberry leaves, fresh sweet potato vine or a mixture of both foliages on intake, digestibility and N retention of growing pigs given a basal diet of broken rice. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 19, Article #136 http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd19/9/chha19136.htm

Göhl B 1981 Tropical Feeds. FAO. http://www.fao.org/ag/AGA/AGAP/FRG/afris/default.htm

González D, González C, Ojeda A, Machadoy W and Ly J 2006

Growth performance of pigs feed sugar cane juice (Saccharum officinarum) and mulberry leaf meal (Morus alba). Archivos Latinoamericanos de Produccion Animal 14 (2): 42-48Kean Sophea and Preston T R 2001 Comparison of

biodigester effluent and urea as fertilizer for water spinach

vegetable. Livestock Research for Rural Development (13) 6:

http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd13/6/kean136.htm

Khieu Borin and Preston T R 1995 Conserving biodiversity

and the environment and improving the well-being of poor farmers in

Cambodia by promoting pig feeding systems using the juice of the

sugar palm tree (Borassus flabellifer). Livestock

Research for rural Development 7 (2) http://www.cipav.org..co/lrrd/lrrd7/2/5.htm

Le Thi Men, Ogle B and Vo Van Son 2000 Evaluation of

water spinach as a protein source for Baxuyen and Large White sows

http://www.mekarn.org/sarpro/lemen.htm

Ly J, Pok Samkol and Preston T R 2002 Nutritional

evaluation of aquatic plants for pigs: pepsin/pancreatin

digestibility of six plant species. Livestock Research for rural

Development 14 (1) 2002 http://www.cipav.org..co/lrrd/lrrd14/1/ly141a.htm.

Mamun M M, Billah M M, Ashek M A, Ahasal M M, Hossain M j

and Sultana T 2003 Evaluation of Diuretic activity of

Ipomoea aquatica (Kalmisak) in mice model study. Journal of Medical

Sciences, pages/rec. No: 395-400. http://de.scientificcommons.org/16289694

Nguyen Xuan Ba, Vu Duy Giang, Le Duc Ngoan and Vu Chi Cuong

2005 Ensiling of mulberry foliage (Morus alba) and the

nutritive value of mulberry foliage silage for goats in central

Vietnam. Workshop-seminar "Making better use of local feed

resources" (Editors: Reg Preston and Brian Ogle) MEKARN-CTU,

Cantho, 23-25 May 2005. Article #24. Retrieved, from http://www.mekarn.org/proctu/ba24.

htm

Pheng Buntha and Chhay Ty 2006 Water-extractable dry

matter and neutral detergent fibre as indicators of whole tract

digestibility in goats fed diets of different nutritive value.

Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 18, Article No.

33. http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd18/3/bunt18033.htm

Prak Kea 2003 Response of pigs fed a basal diet of water

spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) to supplementation with oil or

carbohydrate. MSc. thesis. Swedish University of Agricultural

Sciences, Uppsala

http://www.mekarn.org/msc2001-03/theses03/contkea.htm

Pathoummalangsy Khamparn and Preston T R 2006 Effect

of a supplement of fresh water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) on feed

intake and digestibility in goats fed a basal diet of cassava

foliage. Livestock Research for Rural Development.

Volume 18, Article #35. Retrieved April 4, 2007, from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd18/3/kham18035.htm

Sanchez M D 1999 Mulberry, an exceptional forage available

almost worldwide. World Animal Review 93(2):

36-46

Tingzing Z, Yunfan T, Guangxien H, Huaizhong F and Ben M

1988 Mulberry cultivation. FAO Agricultural Series Bulletin

73/1. Rome pp 127

Vu Chi Cuong, Pham Kim Cuong and Pham Hung Cuong 2005

The nutritive value of mulberry leaf (Morus alba) and effects of

part replacement of cotton seed with fresh mulberry leaf in diets

for growing cattle. Workshop-seminar "Making better use of local

feed resources" (Editors: Reg Preston and Brian Ogle) MEKARN-CTU, Cantho, 23-25May

2005. Article #14. Retrieved.

http://www.mekarn.org/proctu/cuon14.

htm

Undersander D, Mertens D R and Theix N 1993 Forage

analysis procedures. National Forage Testing Association. Omaha pp

154

Wang T C and Fuller M F 1989 The optimum dietary amino acid pattern for growing pigs. British Journal of Nutrition. 62, 17-89