Effect of replacing soybean meal by a mixture of

taro leaf silage and water spinach on reproduction

and piglet performance in Mong Cai gilts

Malavanh Chittavong, T R Preston*and Brian Ogle**

Faculty of Agriculture,

National University of Laos (NUOL),

Vientiane city,Lao PDR

malavanc@yahoo.com

* UTA, TOSOLY, AA #48, Socorro,

Santander, Colombia

** SwedishUniversity of

Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Nutrition and

Management,

PO Box 7024, 750 07, Uppsala,

Sweden

Abstract

Fifteen Mong Cai gilts weighing 46±3.9 kg at service were used in a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD), with five replications of three treatments: TW0, 100% of supplementary protein supplied by soybean meal; TW50, 50% of supplementary protein supplied by soy bean meal and 50% by a mixture of ensiled taro leaves and water spinach, and TW100, 100% of supplementary protein supplied by a mixture of ensiled taro leaves and water spinach. In the pregnancy period the feed was restricted to 1.5% of live weight. In the lactation period the gilts were fed increasing amounts of the same diet up to five days after farrowing, and from then onwards feeds were offered ad libitum.

Total dry matter (DM) intake decreased slightly with increased amounts of the mixture of taro leaf silage and water spinach. Live weights at farrowing and weaning declined as the amount of the mixture of taro leaf silage and water spinach increased. The feed conversion ratios (FCR) for treatments TW0, TW50 and TW100 were 3.09, 3.96 and 5.02 kg feed/kg gain, respectively. Live weight loss and percentage live weight loss in lactation were not affected by diet. The number of piglets born alive and at weaning did not differ among treatments (P>0.05). However, live weights of the litter at birth and weaning and weights of individual piglets declined as the foliages replaced soybean meal. Mortality to weaning ranged from 10.2 (TW0) to 7.5% (TW50) and was not affected by the treatments.

It is concluded that reproduction in the Mong Cai breed, measured as numbers of piglets born alive and weaned, and the interval from weaning to estrus was satisfactory when taro leaf silage and water spinach replaced soybean meal. However, weights of piglets at weaning decreased, with a linear trend from 35.9 to 25.1 kg as the soybean was replaced by the forages.

Key words: Mong Cai gilts, piglet performance,

reproduction, taro leaf silage, water spinach

Introduction

Pigs are widely kept throughout the country of Laos, with 64

percent of all households involved in pig production (Kaufmann et

al 2003). The number of pigs kept by smallholders varies

between an average of 1.4 and 3.7 animals per household, depending

on the region (Kaufmann et al 2003). Pigs are normally raised in a

free-range system, and supplemented by rice bran and other

household waste products (http://clubs.uow.edu.au/clubs_websites/oxfam/Why%20Pigs.pdf).

There are some large-scale pig enterprises close to Vientiane, but

these use purchased concentrate feeds, which are not a viable

option for small-scale farmers in the remote upland

areas.

In view of the increasing costs of concentrate feeds, and

especially protein concentrates such as soybean and fish meal,

recent research in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos has been directed to

the use of leaves from crops such as cassava (Hang and Preston

2005; Chhay et al 2005), sweet potato (An 2004; Malavanh and

Preston 2006), and mulberry (Phiny et al 2003), and water plants

such as water spinach (Men et al 2000; Ly 2002) and duckweed (Rodriguez

and Preston 1996; Hang 1998). Recent research has shown that fresh

water spinach was more palatable than cassava leaves for growing

pigs, as reflected in higher total DM intake, and the proportion of

the diet (47%) provided by the leaves. Digestibility of dry matter,

organic matter, N and crude fibre was higher in diets with water

spinach than in those with cassava leaves (Chhay and Preston 2005).

Taro leaves (Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott) are rich in vitamins and minerals. They are a good source of thiamin, riboflavin, iron, phosphorus and zinc, and a very good source of vitamin B6, vitamin C, niacin, potassium, copper and manganese http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taro).Leaves from Taro (Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott and Alocacia macrorrhiza) and New Cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium) are traditionally used in pig diets by small-scale farmers in many tropical countries. A preliminary report from Colombia (Rodríguez et al 2006) showed that weight gains in young pigs fed a sugar cane juice diet were the same when the supplementary protein was from a 50:50 mixture of fresh leaves of New Cocoyam and soybean meal compared with soybean meal as the only protein source. Recent research from Vietnam (Duyet et al 2006) showed that there were no differences in live weight loss during lactation and days to first oestrus in Mong Cai sows when all the soybean meal was substituted by a mixture of forage protein sources (water spinach, cassava and sweet potato leaves). In contrast, Large White sows showed a significant deterioration in these traits when all the supplementary protein came from the leaves (Duyet et al 2005).

The present experiment aimed to evaluate the effect of

protein-rich leaves as replacement for soybean meal on the

performance of Mong Cai gilts during gestation and lactation.

Materials and methods

Location and

climate

The experiment was carried out from June 2006 to January 2007 at the Faculty of Agriculture, National University of Laos (NUOL), situated about 32 km from Vientiane city, Lao PDR. The mean daily temperature in the area at the time of the experiment was 27 oC (range 22-32 oC).

Experimental animals and

design

Fifteen Mong Cai gilts, with an average live weight at service of 46±3.9 kg, were used in the experiment, and were followed for one complete reproductive cycle. The gilts were imported from Vietnam.

There were three treatments:

-

TW0:100% of supplementary protein supplied by soybean meal (no green foliage supplied).

-

TW50:50% of supplementary protein supplied by soybean meal and 50% by a mixture of ensiled taro leaves and water spinach (equal parts of each foliage on DM basis).

-

TW100:100% of supplementary protein supplied by a mixture of ensiled taro leaves and water spinach (equal parts of each foliage on DM basis).

The experiment was done according to a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) with five replications of each treatment. The gilts were from five litters, with three gilts from the same litter randomly allocated to each treatment. All the gilts were of similar initial body weight.

Housing

The pigs were housed in individual pens made from wood, in an open-sided building with a thatch roof of Imperata grass. The size of each pen was 2.0*1.5m.

Procedure

The energy component of the diet was broken rice and cassava root silage. The composition of the vitamin-mineral premix is shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Composition of the vitamin-mineral premix supplied |

|

|

Item |

per kg |

|

Vitamin-mineral premix |

|

|

Vitamin A, million IU |

10.0 |

|

Vitamin D3, million IU |

2.50 |

|

Vitamin E, IU |

5000 |

|

Vitamin K3,g |

1.60 |

|

Vitamin B1, g |

1.20 |

|

Vitanin B2, g |

3.20 |

|

Vitamin B6, g |

1.20 |

|

Niacin, g |

5.00 |

|

Pantothenic acid,g |

4.00 |

|

Folic acid, g |

5.00 |

|

Biotin, g |

0.12 |

|

Vitanmin C, g |

30.0 |

|

Additives and preservatives, g |

12.0 |

|

Other, kg |

1.00 |

|

Mineral premix |

|

|

Manganese, g |

5.40 |

|

Iron, g |

14.2 |

|

Copper, g |

1.00 |

|

Zinc, g |

2.90 |

|

Sodium, g |

3.90 |

|

Iodine |

19.0 |

|

Potassium, mg |

0.90 |

|

Cobalt, mg |

1.10 |

|

Other, g |

1.00 |

Leaves of taro were purchased in Nonveng village, Hatchaifong district, Vientiane City, and made into silage, using molasses (4%, fresh basis). This was found to be the most suitable level of molasses from the results of Chittavong Malavanh et al (2008). The silage was stored for 21 days in plastic bags to ensure complete fermentation. Some of the water spinach was grown in the Faculty farm; but most was purchased from farmers in the area around the Faculty of Agriculture, National University of Laos. Prior to feeding it was chopped into small pieces and mixed with taro leaf silage and the other ingredients of the diet (cassava root silage and broken rice). The mixed feeds were given to the pigs in 3 meals daily (7:30, 11:30 and 16:30h). Water was permanently supplied through drinking nipples.

Management and

feeding

The Mong Cai gilts were mated at third estrus by natural mating with the same Mong Cai boar. The feeding level was at 4% of live weight (DM basis) until pregnancy was confirmed, after which it was restricted to 1.5% of live weight. In the lactation period the gilts were fed increasing amounts up to five days after farrowing, and from then onwards feeds were offered ad libitum.

Measurements

The gilts were weighed at intervals of 2 weeks during pregnancy. They were weighed after farrowing and then every 2 weeks until the end of lactation (42 days). Piglets were weighed at birth and then every 2 weeks to weaning. Feed intake and live weight gain were recorded during the gestation and lactation periods. Litter size at birth and at weaning, birth weight and weaning weight, mortality of the piglets at birth, live weight changes of the sows during lactation, and interval from weaning to oestrus were also calculated.

Samples of taro leaves were taken at the time of ensiling. Samples of water spinach, cassava root and of broken rice were taken for analysis when they were purchased.

Chemical analyses

Feed samples were analysed for dry matter by micro-wave radiation (Undersander et al 1993). Nitrogen and crude fibre were determined according to AOAC (1990).

Statistical

analysis

The data were analyzed using the General Linear Models procedure of ANOVA in the MINITAB 13.31 program (2000). Sources of variation were blocks, treatments and error.

Results

Ingredient and chemical composition of

the diets

The taro leaf silage and fresh water spinach had DM contents of 20.2 and 8.19 %, respectively, and crude protein (CP) contents of 19.0 and 18.8 % on a DM basis, respectively. The chemical composition of the diets and planned ration formulation are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

|

Table 2. Chemical composition of ingredients (% dry basis) |

||||||

|

Ingredient |

DM |

CP |

CF |

Ash |

Oxalic acid, % |

HCN, mg/kg DM |

|

Water spinach |

8.19 |

18.8 |

16 |

15.1 |

|

|

|

Taro leaf silage |

20.2 |

19 |

13.2 |

11.6 |

0.30 |

|

|

Soybean meal |

87.8 |

41.8 |

8.02 |

7.4 |

|

|

|

Cassava root silage |

43.7 |

1.12 |

4.12 |

3.5 |

|

325 |

|

Broken rice |

86.9 |

5.74 |

2.78 |

0.81 |

|

|

|

Salt |

95.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Premix |

98.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Feed and nutrient intake

Feed and nutrient intakes are presented in Table 3 and 4.

|

Table 3. Formulation of diets, % of DM |

|

||

|

Ingredient |

TW0 |

TW50 |

TW100 |

|

Broken rice |

37.0 |

33.9 |

18.5 |

|

Cassava root silage |

49.5 |

44.6 |

48.0 |

|

Taro leaf silage |

0.00 |

7.00 |

16.0 |

|

Water spinach |

0.00 |

7.00 |

16.0 |

|

Soybean meal |

12.0 |

6.00 |

0.00 |

|

Premix |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

|

Salt |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.50 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

% Crude protein |

10.0 |

10.0 |

10.0 |

|

Table 4.

Effect of replacing soy bean meal by a mixture of taro leaf silage

and water spinach on daily |

|||||

|

Parameter |

Dietary treatment* |

SEM |

P-value |

||

|

TW0 |

TW50 |

TW100 |

|||

|

No of gilts |

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

Pregnancy period |

|

|

|

|

|

|

DM, g/day |

946a |

910a |

794b |

34.5 |

0.022 |

|

CP, g/day |

84.8a |

82.0a |

72.2b |

3.05 |

0.031 |

|

CF, g/day |

39.6b |

52.0a |

58.0a |

1.82 |

0.000 |

|

CP, g/kg DM |

89.8 |

90.6 |

90.2 |

0.42 |

0.440 |

|

DM/kg LW |

14.6 |

15.2 |

14.8 |

2.80 |

0.340 |

|

Lactation period |

|

|

|

|

|

|

DM, g/day |

2549 |

2434 |

2111 |

261.4 |

0.492 |

|

CP, g/day |

244 |

236 |

203 |

25.4 |

0.493 |

|

CF, g/day |

142 |

171 |

182 |

17.2 |

0.277 |

|

CP, g/kg DM |

98.8 |

98.0 |

100 |

1.42 |

0.620 |

|

DM/kg LW |

38.0 |

37.4 |

29.8 |

4.08 |

0.340 |

|

a,b Mean values within rows with different superscript letters are significantly different (P<0.05); * See Table 3. |

|||||

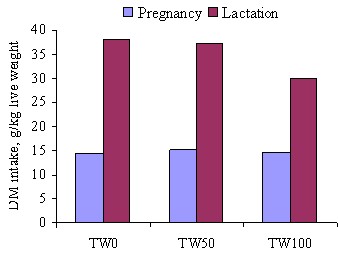

Total DM intake decreased slightly with increased amount of the mixture of taro leaf silage and water spinach. In pregnancy, the daily DM intake was highest in diet TW0 (946 g/day), which was higher (P<0.05) than in the other two diets (910 and 794g/day for diet TW50 and TW100, respectively) (Figure 1).

|

|

|

Figure 1. Mean intakes of DM (g/kg live weight), during

pregnancy and lactation |

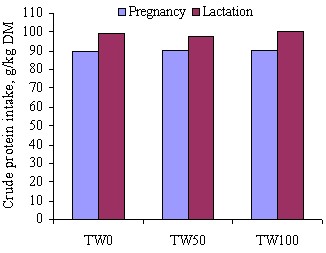

The CP intake was highest in diet TW0 (85 g/day) (P<0.05) (Figure 2).

|

|

|

Figure 2. Mean intakes of crude protein (g/kg DM) during

pregnancy and lactation |

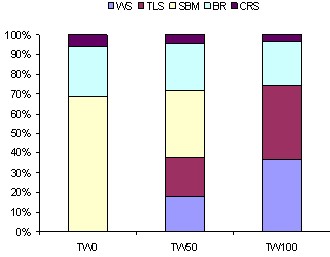

In the lactation period daily DM and CP intakes were not different among diets (P>0.05).The proportion of the diet CP derived from the individual ingredients during pregnancy is shown in Figure 3. The protein was supplied almost entirely by soybean meal and the mixture of taro leaf silage and water spinach.

|

|

|

Figure 3. Proportion of diet crude protein derived from

individual ingredients* during pregnancy |

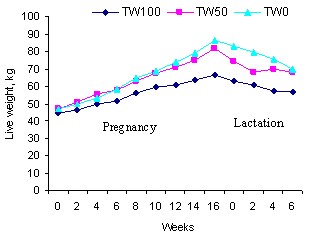

Live weight changes in pregnancy

Live weight changes of the Mong Cai gilts are presented in Table 5 and Figure 4. There were no significant differences among treatments in live weight at service (P>0.05). However, live weights at farrowing declined as the proportion of the mixture of taro leaf silage and water spinach increased (P<0.05). The live weight increase of the gilts in treatment TW0 and average daily gain (ADG) throughout pregnancy were higher than in TW100 (P<0.01).

|

Table 5. Effect of replacing soybean meal by a mixture of taro leaf silage and water spinach on the performance of Mong Cai gilts in pregnancy |

|||||

|

Parameter |

TW0 |

TW50 |

TW100 |

SEM |

P-value |

|

Live weight, kg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

At service |

47.1 |

46.8 |

44.7 |

1.71 |

0.579 |

|

After farrowing |

82.8a |

74.2ab |

63.1b |

3.84 |

0.012 |

|

Change in pregnancy |

35.7a |

27.4ab |

18.4b |

3.14 |

0.007 |

|

Pregnancy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ADG, g |

313a |

242ab |

163b |

26.9 |

0.007 |

|

FCR, kg feed DM/kg gain |

3.09a |

3.96ab |

5.02b |

0.37 |

0.010 |

|

Length of pregnancy, days |

114 |

113 |

112 |

0.77 |

0.287 |

|

a, b Mean values within rows with different superscript letters are different at P<0.05 |

|||||

|

|

|

|

The length of pregnancy was 114.2, 113.4 and 112.4 days in

treatments TW0, TW50 and TW100, respectively (P>0.05). The mean feed conversion ratios (FCR) for treatments TW0, TW50

and TW100 were 3.09, 3.96 and 5.02 kg feed/kg gain, respectively

(P<0.01).

Live weight changes of the sows in

lactation

Live weight at weaning of the sows was highest in diet TW0 (69.9 kg) and lowest in diet TW100 (56.5 kg) (P<0.05). Live weight loss and percentage of live weight loss in lactation were not affected by the diet (P>0.05) (Table 6).

|

Table 6. Effect of replacing soy bean meal by a mixture of taro leaf silage and water spinach on weight changes in lactation |

|||||

|

|

TW0 |

TW50 |

TW100 |

SE |

P-value |

|

Live weight, kg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

After farrowing |

82.8a |

74.2ab |

63.1b |

3.33 |

0.009 |

|

At weaning |

69.9a |

68.0ab |

56.5b |

3.26 |

0.040 |

|

Weight loss in lactation period |

13.0 |

6.20 |

6.80 |

2.20 |

0.111 |

|

Weight loss/day |

0.31 |

0.15 |

0.16 |

|

|

|

% weight loss |

15.0 |

8.00 |

10.2 |

2.59 |

0.209 |

|

Weaning to oestrus, days |

6.60 |

6.60 |

6.40 |

0.24 |

0.804 |

|

a, b Mean values within rows with different superscript letters are different at P<0.05 |

|||||

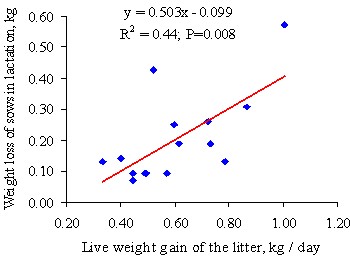

Live weight loss of the sows during lactation was positively and linearly related to the growth rates of their litters (Figure 4 and 5).

|

|

|

Figure 5. Live weight changes of the sows throughout the

reproductive cycle |

Reproductive traits

All experimental sows returned to oestrus within around 6 days after weaning, and mean weaning to estrus interval did not differ among treatment (P>0.05).

Piglet performance in lactation

Litter size and piglet live weights at birth, 28 days and weaning are shown in Table 7.

|

Table 7.

Effect of replacing soy bean meal by a mixture of taro leaf silage

and water spinach |

|||||

|

|

TW0 |

TW50 |

TW100 |

SEM |

P-value |

|

At birth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total litter size |

10.8 |

10.8 |

10.6 |

1.09 |

0.989 |

|

Total litter size live born |

10.2 |

10.0 |

9.40 |

1.06 |

0.860 |

|

% mortality |

5.56 |

7.87 |

11.0 |

3.41 |

0.546 |

|

Total litter weight, kg |

5.12 |

5.96 |

4.95 |

0.54 |

0.405 |

|

Mean live weight, kg |

0.47 |

0.55 |

0.46 |

0.03 |

0.164 |

|

At 28 days |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total litter size |

9.60 |

9.40 |

8.60 |

1.00 |

0.759 |

|

Total litter weight, kg |

26.5 |

22.9 |

18.1 |

2.56 |

0.105 |

|

% mortality |

5.72 |

5.48 |

8.44 |

3.26 |

0.780 |

|

Litter weight change, kg |

21.4 a |

16.9ab |

13.1b |

2.08 |

0.048 |

|

Mean piglet live weight, kg |

2.81 |

2.54 |

2.01 |

0.23 |

0.071 |

|

At weaning |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total litter size at weaning |

9.20 |

9.20 |

8.60 |

0.98 |

0.883 |

|

Total litter weight at weaning, kg |

35.9a |

30.9ab |

25.1b |

1.80 |

0.009 |

|

Litter weight change, kg |

30.8a |

24.9ab |

20.1b |

1.56 |

0.004 |

|

Mean piglet live weight, kg |

3.96 |

3.58 |

2.85 |

0.33 |

0.110 |

|

% mortality, birth to weaning |

10.2 |

7.5 |

8.4 |

3.43 |

0.851 |

|

a, b Mean values within rows with different superscript letters are different at P<0.05 |

|||||

The total mean number of piglets born per litter was 10.8, 10.8 and 10.6 in treatments TW0, TW50 and TW100, respectively (P>0.05). The number of piglets born alive was not different (P>0.05) among treatments. Percentage mortality at birth was numerically higher on the TW100 diet but the differences were not significant (P= 0.55, 0.78 and 0.85 at birth, 28 days and at weaning). The total number of piglets, live weight and percentage mortality at 28 days were not different among treatments (P>0.05). The highest litter live weight was for the diet TW0 (21.4 kg/litter), and lowest in diet TW100 (13.1 kg/litter) (P<0.05).

The total mean number of piglets per litter at weaning was 9.20, 9.20 and 8.60 in TW0, TW50 and TW100, respectively (P>0.05). The total weight of piglets weaned was highest in diet TW0 (35.9 kg/litter) and lowest in diet TW100 (25.1 kg/litter) (P<0.05).

Discussion

Feed intake and live weight changes of

the gilts

The use of a high level of inclusion of a mixture of taro leaf silage and water spinach in the diet of Mong Cai gilts could be expected to reduce the dry matter feed intake, mainly due to the bulkiness and possibly also due to lower palatability of this feed, as was the case. This is in agreement with Rodríguez et al (2006), who reported that the DM intake was reduced when the percentage of New Cocoyam in the diet was increased to 100%. Recent research from Pham Sy Tiep et al (2006) showed that the feed intake was highest for a diet with 10% Alocasia macrorrhiza leaves and lowest for a diet with 15% Alocasia macrorrhiza leaves), which suggested that the highest level of inclusion of ensiled Alocasia macrorrhiza leaves had a negative effect on palatability.

One sow in the treatment TW100 farrowed 5 days before the

expected farrowing date, which resulted in a shorter mean length of

pregnancy for TW100, although the difference compared to the other

two treatments was not significant. The length of pregnancy in

this experiment is similar to the results of Loc et al (2000), who

also reported that the length of pregnancy was not different among

treatments when increasing levels of ensiled forages were included

in the diets of Mong Cai sows.

Weight losses of sows during the 42 days lactation were 0.31, 0.15 and 0.16 kg/day for TW0, TW50, and TW100, respectively, which is similar to the findings of Nga et al (2000), who reported that the mean weight loss of Mong Cai sows during a 49 day lactation was 12.6 kg (0.21 kg/day). The sows had been fed during pregnancy a diet with 10.3 % CP in DM, mainly derived from cassava leaf meal and water spinach. During lactation, voluntary feed intake of highly prolific sows is frequently inadequate to meet nutrient requirements for maintenance and milk yield, and these sows must mobilize fat and protein reserves (O'Grady et al 1985; Noblet et al 1990). Revell et al(1998) reported that body weight loss from sows during lactation depended on the protein content of the diet offered during lactation but not on body composition at farrowing. Sows offered a high protein diet during lactation (19.0% CP and 15.6 MJ DE/kg as fed) lost on average 4.3 kg during the four weeks of lactation (0.15 kg live weight/day), while those offered a low protein diet (7.9% CP and 15.5 MJ DE/kg as fed) lost on average 30.8 kg during lactation (1.1 kg/day). Low protein intake during lactation was also demonstrated to increase body protein loss (Jones and Stahly 1999) and to reduce reproductive performance (King and Williams 1984; Brendemuhl et al 1987; Yang et al 2000), but this was not the case in the present study, probably because of the lower nutrient requirements of indigenous sows such as the Mong Cai.

The estimated requirements for crude protein are presented in Table 8 for diets with an "ideal" protein (Speer 1990) compared with conventional diets based on maize and soybean (NRC 1988).

|

Table 8. Estimates of crude protein required for diets with an “ideal” protein (from Speer 1990) and conventional diets based on maize and soybean meal (from NRC 1988) for the Mong Cai gilts in the present study |

||||||||

|

|

Gestation |

Lactation |

||||||

|

LW, kg |

Crude protein, g/day |

LW, kg |

Crude protein, g/day |

|||||

|

Speer |

NRC |

This study |

Speer |

NRC |

This study |

|||

|

TW0 |

66.3 |

51 |

80.3 |

85.0 (62) |

74.8 |

160 |

214 |

244 (178) |

|

TW50 |

64.3 |

49.5 |

77.8 |

82.0 (66) |

68.5 |

147 |

196 |

236 (190) |

|

TW100 |

56.2 |

43.3 |

68 |

72 |

58 |

124 |

166 |

203 |

|

Figures in brackets are adjusted for the observed apparent crude protein digestibility (Malavanh et al 2007) |

||||||||

In all the diets, the amounts of CP consumed were slightly above the recommended levels according to NRC (1988) and much higher than requirements for a diet with an ideal protein. However, if the reduced protein digestibility is taken into account the intakes in the present study would be midway between the requirements according to the "ideal" protein and those of NRC (1988).

Although digestible energy (DE) contents of the diets were not

calculated the low DE intakes both in pregnancy and lactation would

probably also have contributed to the significantly lower LW gains

in pregnancy and higher lactation losses of the sows on the TW100

treatment.

All sows returned to oestrus within 6 days after weaning,

despite the low protein content of the diets, which is in

agreement with the results of Mejia-Guadarrama et al

(2002), who found that crossbred sows (Pietrain x (Large

White x Landrace)) returned to oestrus within 9 days after weaning,

and that the interval weaning to estrus did not differ between

experimental groups fed high or low levels of protein (20% CP and

1.08% lysine or 10% CP and 0.5% lysine). The results from this

experiment contrast with those of Nga et al (2000) who reported

that Mong Cai sows returned to estrus within 15.8 days after

weaning at 49 days, when fed 10.3 % of CP from cassava leaf

meal and water spinach during pregnancy.

Piglet performance

Duyet et al (2006) reported that litter weight at 21 days was

reduced from 28.3 to 23.7 in purebred piglets from Mong Cai sows

when the soybean meal was replaced by a mixture of fresh leaves

(from cassava, water spinach and sweet potato) but litter size was

not affected. These finding are similar to the results in the

present study, where at 28 days the litter weight was reduced from

26.5 to 18.1 kg. The greater difference in our study may have been

because creep feed was not offered until 30 days after birth. Size

of litter was not affected by the replacement of soybean with the

forages, which is in agreement with the findings of Duyet et al

(2006). However, in Baxuyen sows fed ensiled cassava roots as the

energy source, supplying fresh duckweed (11% in the DM of the diet)

as partial replacement of the protein supplement led to higher

number of piglets born alive and heavier litter weights at birth

and at weaning (Men et al 1997). The results imply that duckweed

protein, as well as being highly digestible (Rodríguez et al

1996), has a good array of essential amino acids. Also duckweed is

a rich source of vitamin A precursors, particularly carotene (Leng

et al 1995), and vitamin A is vitally important for reproduction.

It is probable that in our study the vitamin A content in the

control diet was adequate to meet the requirement of the pregnant

sows, and so there was no improvement found in litter size when

additional vitamin A was supplied as green forage.

Conclusions

-

A mixture of taro leaf silage and water spinach can replace 100 % of soybean meal in pregnancy and lactation diets for Mong Cai gilts without affecting sow reproduction, measured as numbers of live piglets born and weaned, and the interval from weaning to estrus.

-

However, weights of piglets at weaning decreased with a linear trend as the soybean was replaced by the forages.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the Swedish International Development

Cooperation Agency, Department for Research Cooperation

(Sida-SAREC) through the regional MEKARN Project, for the financial

support of this study.

We would also like to thank the Faculty of

Agriculture, National University of Laos for allowing and helping us to carry out this

experiment. The authors thank Mr Bounlerth Syvilai for analytical

assistance in the laboratory of the Faculty of Agriculture.

References

AOAC 1990 Official Methods of Analysis. Association of

Official Analytical Chemists. 15th Edition (K Helrick

editor). Arlington pp 1230.

An LV 2004 Sweet potato leaves for growing pigs: Biomass

yield, digestion and nutritive value. Doctoral thesis, Swedish

University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala. 2004. http://diss-epsilon.slu.se/archive/00000639/01/Agraria470.pdf

Brendemuhl

J H, Lewis A and Peo E R Jr 1987 Effect of

protein and energy intake by primiparous sows during lactation on

sow and litter performance and sow serum thyroxine and urea concentrations. Journal of Animal Science 64:1060-1069

Chhay T and Preston T R 2005 Effect of water spinach and

fresh cassava leaves on intake, digestibility and N retention in

growing pigs; Workshop-seminar "Making better use of local

feed resources" MEKARN-CTU, Cantho, 23-25 May, 2005.

Duyet H N, Thuan T T and Son N D 2005 Effects on sow

reproduction and piglet performance of replacing soybean meal by a

mixture of sweet potato leaves, water spinach and fresh cassava

foliage in the gestation and lactation diets of Mong Cai and

Yorkshire sows. Workshop-seminar

"Making better useof local feed resources" (Editors: R

Preston and B Ogle) MEKARN-CTU, Cantho, 23-25 May, 2005.

http://www.mekarn.org/proctu/duye41.

htm

Duyet H N, Thuan T T and Son N D 2006 Effects on sow

reproduction and piglet performance of replacing soybean meal by a

mixture of sweet potato leaves, water spinach and fresh cassava

foliage in the gestation and lactation diets of Mong Cai and

Yorkshire sows. Workshop-seminar "Forages for Pigs and Rabbits"

MEKARN-CelAgrid, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 22-24 August, 2006. Article

# 17. Retrieved , from

Hang D T 1998 Ensiled cassava leaves and duckweed as

protein sources for fattening pigs on farms in Central Vietnam.

Livestock Research for Rural Development.Volume 10, Number

3. http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd10/3/hang1.htm

Hang D T and Preston T R 2005 The effects of simple

processing methods of cassava leaves on HCN content and intake by

growing pigs. Workshop-seminar "Making better use of local

feed resources" MEKARN-CTU, Cantho, 23-25 May, 2005. http://www.mekarn.org/proctu/hang4

.htm

Jones D B and Stahly T S 1999 Impact of amino acid nutrition during lactation on body nutrient mobilization and milk nutrient output in primiparous sows. Journal of Animal Science 77:1513-1522 http://jas.fass.org/cgi/reprint/77/6/1513.pdf

Kaufmann B, Wienand J, Teufel N and Valle Zarate A 2003 Livestock Production Systems in South and South East Asia, Hohenheim University Institute for Animal Production in the Tropics and Subtropics, Hohenheim. Unpublished manuscript

King R H and Williams I H 1984 The effect of nutrition on

the reproductive performance of first-litter sows. 1. Feeding level

during lactation and between weaning and mating. Animal Production

38:241-247

Leng R A, Stambolie J H and Bell R 1995

Duckweed

- a potential high-protein feed resource for domestic animals and

fish. Livestock Research For Rural

Development. (7)1. http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd7/1/3.htm

Ly J 2002 The effect of methionine on digestion indices

and N balance of young Mong Cai pigs fed high levels of ensiled

cassava leaves. Livestock Research for Rural Development.

(14) 2: http://www.cikpav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd14/6/Ly146.htm

Loc N T, Ly N T H, Thanh V T K and Duyet H N 2000 Ensiling techniques and evaluation of cassava leaf silage for Mong Cai sows in Central Vietnam. National seminar-workshop "Sustainable Livestock Production on Local Feed Resources" SIDA-SAREC - University of Agriculture and Forestry, National of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 18-20 January, 2000 http://www.mekarn.org/sarpro/locmay30.htm

Malavanh Chittavong and Preston T R 2006 Intake

and digestibility by pigs fed different levels of sweet potato

leaves and water spinach as supplements to a mixture of rice bran

and cassava root meal. Livestock Research for Rural

Development. http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd18/6/mala18086.htm

Mejia-Guadarrama C A, Pasquier A, Dourmad J Y, Prunier A and Quesnel

H 2002 Protein (lysine) restriction in

primiparous lactating sows: Effects on metabolic state,

somatotropic axis, and reproductive performance after weaning. Journal of Animal Science 2002. 80:3286-3300

Men L T, Ogle B and Son V V 2000 Evaluation of water

spinach as a protein source for Baxuyen and Large White sows.

National seminar-workshop "Sustainable Livestock Production on

Local Feed Resources" SIDA-SAREC - University of Agriculture and

Forestry, National of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 18-20 January,

2000

Men L T, Van B H, Chinh M T and Preston T R 1997

The effect of dietary protein level and duckweed (Lemna spp)

on reproductive performance of pigs fed a diet of cassava root or

cassava root meal. National seminar-workshop "Sustainable Livestock

Production on Local Feed Resources" SIDA-SAREC - University of

Agriculture and Forestry, National of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam,

10-14 September, 1996.

MINITAB 2000 Minitab reference Manual release 13.31

Nga L Q, Magnusson U and Ogle B 2000 Evaluation of the

reproductive performance of an indigenous pig breed in Vietnam

(Mong Cai) and a cross-breed fed on local and conventional feeds.

National seminar-workshop "Sustainable Livestock Production on

Local Feed Resources" SIDA-SAREC - University of Agriculture and

Forestry, National of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 18-20 January,

2000.

Noblet J, Dourmad J Y and Etienne M 1990 Energy

utilization in pregnant and lactating sows: Modeling of energy

requirements. Journal of Animal Science 68:562-572

NRC 1998 Nutrient requirement for swine. National Academy

Press; Washington, DC.

O'Grady J F, Lynch P B and Kearney P A 1985 Voluntary

feed intake by lactating sows. Livestock Production Science

12:355-365

Pham Sy Tiep, Nguyen Van Luc and Dang Hoang Bien 2005 Processing and use of Alocasia macrorrhiza (taro) roots for fattening pigs under mountainous village conditions; Workshop-seminar "Making better use of local feed resources" (Editors: Reg Preston and Brian Ogle) MEKARN-CTU, Cantho, 23-25 May, 2005. Article #44. RetrievedOctober 23, 106, from http://www.mekarn.org/proctu/tiep44.htm

Phiny C, Preston T R and Ly J 2003 Mulberry (Morus

alba) leaves as protein source for young pigs fed rice-based

diets: Digestibility studies; Livestock Research for Rural

Development (15) 1. http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd15/1/phin151.htm

Revell D K, Williams I H, Mullan B P, Ranford J L and Smits R

J 1998 Body composition at farrowing and nutrition during

lactation affect the performance of primiparous Sows: I. Voluntary

feed intake, weight loss, and plasma metabolites. Journal of Animal

Science 76:1729-1737

Rodríguez L, Peniche I and Preston T R 2006

Digestibility and nitrogen balance in growing pigs fed a diet of

sugar cane juice and fresh leaves of New Cocoyam

(Xanthosomasagittifolium) as partial or complete replacement

for soybean protein. Workshop-seminar "Forages for Pigs and

Rabbits" MEKARN-CelAgrid, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 22-24 August,

2006. Article # 16. Retrieved , from http://www.mekarn.org/proprf/rodr2

.htm

Rodríguez L and Preston T R 1996 Comparative

parameters of digestion and N metabolism in Mong Cai and Mong

Cai*Large White cross piglets having free access to sugar cane

juice and duck weed. Livestock Research For Rural

Development (8)1. http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd8/1/lylian.htm

Speer V C 1990 Partitioning nitrogen and amino acids for

pregnancy and lactation in swine: A review. Journal of Animal

Science 68:553-561

Undersander D, Mertens D R and Theix N 1993 Forage analysis procedures. National Forage Testing Association. Omaha pp 154

Yang H, Pettigrew J E, Johnston L J, Shurson G C and Walker R D 2000 Lactational and subsequent reproductive responses of lactating sows to dietary lysine (protein) concentration. Journal of Animal Science 78:348-357 http://jas.fass.org/cgi/reprint/78/2/348.pdf