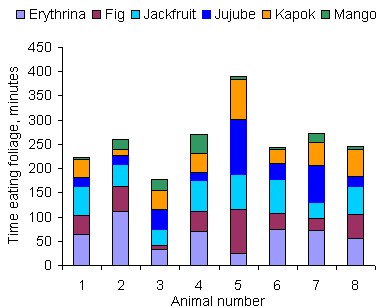

Figure 1. Time in minutes spent eating each foliage during the observation day (9 h)

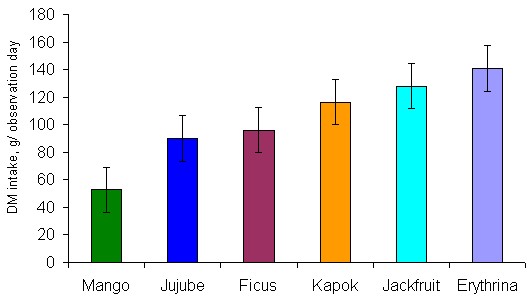

Figure 2. The number of times per day the animals changed from one foliage to another

|

MEKARN Regional Conference 2007: Matching Livestock Systems with Available Resources |

Chemical composition, digestibility, N retention and feed intake characteristics of some tropical foliage species used for local goats were studied.Twelve local male goats with an initial body weight (BW) of 14.6 kg and around 3.5 months of age, were randomly allocated to six treatments in a repeated randomized complete block design with 3 periods. The treatments were foliages from Erythrina (Erythrina variegata), Fig (Ficus racemosa), Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus), Jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill), Kapok (Ceiba pentandra) and Mango (Mangifera indica), which were offered ad libitum at the level of 130 % of the average daily feed intake.

The Erythrina foliage had a low content of DM and condensed tannins (CT) and a high concentration of crude protein (CP) in leaves plus petioles, 193 g/kg DM, and stem, while the Mango foliage had a low CP, 69 g/kg DM, and high DM content. The other foliages were intermediate between Erythrina and Mango. High content of CT was found in the leaves plus petioles of Jackfruit foliage and in the stem of Fig and Mango foliage. There was a significant difference in feed intake, nutrient intake, apparent digestibility and N retention between treatments (P<0.05), with Erythrina, Jackfruit and Kapok foliage being significantly higher in those parameters than Fig, Jujube and Mango foliage.

In a subsequent experiment, the Fig, Jujube and Mango foliages were offered ad libitum together with fresh water spinach at 0.5% of LW (DM basis). DM and CP intake, apparent digestibility and N retention were all markedly increased compared to feeding these foliages as sole feeds in the previous experiment.

In a third experiment, the feed intake and selective behaviour of eight local male goats (15.7 kg and 7 months of age) were studied by following each goat during 9 hours per day with six foliages. Three types of foliage species: Erythrina, Jackfruit and Kapok foliage, were selected more often and more time was spent eating these foliages, resulting in higher total feed intake compared to Fig, Jujube and Mango foliage, but the Jujube foliage was preferred by some of the goats. The goats were very individual in their selective and intake behaviour.

In the Lao PDR, more than 70% of the total production from livestock such as goats, cattle, pigs and poultry comes from smallholders using traditional management systems. The main feed resources for the ruminants are native grasses, legumes and tree leaves that are available in the natural grassland and forests (Phengsavanh.2003).

Goats have a habit of selecting their feed carefully when eating and are considered to be agile feeders (Dumont et al 1995; Ngwa et al..000). According to Steele (1996) goats are continuously searching for feed and are more satisfied when they have a whole range of different plants available including trees, shrubs and grasses. However, goats are also considered to be very fastidious and even when having a very large selection to choose between they will only consume the most nutritious feed available (Van Soest., 1982; Fajemisin et al 1996). According to Steele (1996) reported that shoots and leaves are preferred to stems when goats are allowed to select. Keskin et al. (2005) showed that goats can spend 26.6 % of their time eating (383 minutes in 24 hours).

There are many kinds of tree fodder, legumes and crops which are important protein resources, for instance foliage from Leucaena, Erythrina, Jackfruit, Kapok and Jujube, sweet potato vines and water spinach. Normally, these green plants are used as traditional feeds in diets for animals, but little is known about their nutritive value, especially the protein availability. Some foliages have been researched, but there are still many types of foliage commonly used as feeds that have not been characterized properly. For example foliage from Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) has been extensively researched in tropical countries. Nguyen Thi Hong Nhan and Preston (1997) found that intake of fresh Jackfruit leaves was higher when fed as a sole feed (3.9 kg/day) than when a supplement of sugar cane juice at levels up to 2 kg/day was given (3.5 kg/day) to dairy goats.

Also Erythrina variegata has been studied to some degree. Simbaya (2002) reported that Erythrina contains 258 g CP and 14.4 MJ per kg DM, which is a high content of CP when compared to other fodder tree and shrub species. Aregheore and Perera (2004) and Kibria et al. (1994) suggested that Erythrina could be used as a protein supplement to improve the nutritional quality of maize stover fed to mature goats, since it has significantly higher digestibility of DM, CP, NDF, OM and energy than Leucaena and Gliricidia.

Kapok (Ceiba pentandra) is a multipurpose tree, which, as the fruit bursts open, exposes a cotton like substance. The seeds, leaves, bark and resin from the Kapok tree are used as traditional medicine for dysentery, fevers, venereal diseases, asthma, menstruation bleeding and kidney diseases. The leaves can be used for animal feed and contain 186 g CP and 884 g OM per kg DM. It has the potential to increase the DM digestibility and voluntary intake of low quality basal diets by supplying a valuable protein source (Theng Kouch et al 2005).

Mango (Mangifera indica) is native to South Asia and is a multipurpose tree. The fruits and the foliage are not only used as food and feed but have also medicinal uses for humans. The foliage is a good potential source of forage to ruminants since it is green all the year round. According to Ajayi et al. (2005) Mango leaves contain 204 g CP/kg DM and when Mango leaves and concentrate were fed as a supplement to a Panicum maximum based diet, DM and CP intake increased as well as daily liveweight gain to 44.6 g/d.

Some foliages are known to be preferred by goats e.g. Jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill), but there is little or no research available. According to Morton (1987) and Reich (1991) fresh Jujube leaves contain a saponin, ziziphin, and from dried leaves a sweetness-inhibiting saponin could be extracted. Nath et al. (1996) reported that Jujube leaves are a rich source of protein and minerals with 140 g CP, 28 g Ca and 1.4 g P per kg DM. Fig (Ficus racemosa) is also an available tree in tropical areas. Schurrie (1990) reported that Fig leaves are related to Jackfruit, Mulberry (Morus spp.) and Chinese Mulberry (Cudrania tricuspidata). According to data analysis from the Faculty of Agriculture Laboratory, NUoL, Laos, Fig foliage has high content of CP, 193 g/kg DM, and 170 g/kg DM of crude fiber.

Water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) is another plant which produces high yields of protein-rich biomass. Water spinach has a high nutritive value for humans and also for animals such as rabbits (Pok Samkol et al 2006), pigs (Chhay Ty and Preston 2005) and goats. According to Peng Buntha and Chhay Ty (2006) the N intake of local goats was 8.84 g/day when fed fresh water spinach, which is higher than when feeding cassava foliage, guinea grass or stylo. Dry matter and N intakes were increased linearly by supplementation with water spinach by 40% compared to feeding cassava alone (Pathoummalangsy and Preston.2006), and water spinach also increased DM digestibility and N retention in local goats.

The aim of these experiments was to analyses the chemical composition of some foliages available for goats and compare intake, digestibility, nitrogen retention and selective behaviour when feeding these foliages either as a sole feed or for foliages with low intake and digestibility, together with water spinach.

The experiments were conducted in the farm of the Livestock and Fisheries Department, Faculty of Agriculture, National University of Laos, 35 km south of Vientiane, Lao PDR. The climate in this area is tropical monsoon with a rainy season between May and October and a dry season from November to April. Average annual rainfall is 2000 mm/year. The two trials were conducted during June to December 2006.

The animals used in the two experiments were 16 local male growing goats, 12 goats for the first digestibility experiment and 4 goats for the second digestibility experiment. The goats were bought in the area around the Faculty of Agriculture, Nabong Campus. The mean and SD of the initial body weight (BW) of the goats was 14.6 (1.4) and 13.4 (2.2) kg, and the age around 3.5 and 6 months in the first and second experiment, respectively. Before starting the experiments, the goats were treated against parasites with injections of Ivermectin solution (1 ml per 4 kg BW) and were vaccinated against Foot and Mouth disease. Feed and water offered to each goat were weighed every morning and the animals were given the feed ad libitum at the level of 130% of the average daily feed intake the previous week. The animals were fed 3 times per day at 08:00 h, 12:00 h and 16:00 h. The minerals offered to each goat were given ad libitum by hanging a mineral block in each cage. The mineral lick block contained 140 g Na, 140 g Ca, 51 g P, 10.5 g S, 22 g K, 10 g Mg, 2.5 g Fe, 900 mg Zn, 350 mg Mn, 400 mg Cu, 90 mg Co, 380 mg I and 12 mg Se, per kg block. The goats were housed in individual metabolism crates made from local materials measuring 0.8 x 0.8 x 0.8 m in width, length and height, respectively. The houses, cages and troughs were cleaned every day.

The experimental feeds used in the first digestibility experiment were foliages from Erythrina (Erythrina variegata), Fig (Ficus racemosa), Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus), Jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill), Kapok (Ceiba pentandra) and Mango (Mangifera indica). In the second digestibility experiment, the feeds used were Water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica), Fig, Jujube and Mango. Each foliage was used in the fresh form, including leaves, petioles and 30 cm of the stem. The foliages were offered hanging, tied to a bamboo stick over the cage and above the feed trough to collect leaves that may have fallen down. The foliages were harvested by cutting trees and shrubs around the Faculty of Agriculture in the morning for feeding at noon and in the afternoon for feeding the next day in the morning. The water spinach was bought from farmers around the Faculty of Agriculture in the morning and weighed for feeding during the whole day.

The first digestibility experiment was a repeated randomized complete block design (RCBD) with 6 treatments (the different foliages fed as the sole feed). The experiment was run for 3 periods (3 repetitions) and each period had 2 blocks. The goats were randomly allocated to the metabolism cages and the foliages. In every period, each foliage was given to 1 animal in each block. The periods consisted of 14 days of adaptation to the diets and 7 days of data collection. Between each period there were 7 days for rehabilitation with good diets such as grass, cassava chips and some foliage supplementation.

The second digestibility experiment was a 4*4 Latin Square design. The treatments were four diets: 1: Water spinach ad libitum (WS), 2: Fig ad libitum + 0.5% of BW as DM Water spinach (FWS), 3: Jujube ad libitum + 0.5% of BW as DM Water spinach (JWS) and 4: Mango + ad libitum + 0.5% of BW as DM Water spinach (MWS). Half of the daily offer of Water spinach was fed at 08:00 h in the morning and half at 16:00 h in the afternoon. Each period of the experiment consisted of 10 days of adaptation to the diets and 5 days of data collection and between each period there was a 3 day period for rehabilitation, with good diets such as grass, cassava chip and some foliage provided.

Feeds offered and refused were recorded individually daily during the whole experimental period. Each foliage, six samples in the first experiment and eight samples in the second experiment, was separated and weighed to estimate the average proportion of leaves plus petiole and stem. During the collection period the refusals were separated into leaves plus petiole and stem in order to measure the selection of the different parts. Water offered and refused was also measured daily. Samples of feed offered were taken twice in each period, resulting in 6 and 8 samples of leaves plus petiole and stem in total in the first and second experiment, respectively. The whole foliage was sampled (divided into leaves plus petiole and stem). Samples of refusals (also divided into leaves plus petiole and stem) were taken individually daily during the data collection periods. The faeces and urine excreted were recorded twice daily at 7:00 h and 17:00 h. At each data collecting time, 10% of the faeces was sampled and frozen at –20oC. Urine was collected in a jar containing 50 ml of 10% sulphuric acid (urine pH<3) to preserve the nitrogen (Chen and Gomes, 1992) and 10% urine was also sampled and stored at 4oC for further analysis.The fresh form of the foliages was analysed for DM, ash, and CP according to AOAC (1990). NDF was determined using the procedure of Goering and Van Soest (1970) and Condensed tannins were analysed according to Makkar et al. (1995).

The data from the intake and digestibility trials were analyzed statistically by using the GLM procedure of Minitab Software, version 13.31 (Minitab.000). Treatment means, which showed significant differences at the probability level of P<0.05, were compared using Tukey’s pairwise comparison procedures.

In the first experiment, the statistical model used was: Yijk = m + Pi + Bj(Pi) + Fk + eijk where Yijk is the dependent variable, Pi is the effect of period, Bj(Pi) is the effect of block in the period, Fk is the effect of treatment (different foliages) and eijk is the random error effect.

In the second experiment, the statistical model used in the analysis was: Yijk = m + Fi + Aj + Pk + eijk where Yijk is the dependent variable, Fi is the effect of treatment, Aj is the effect of animals, Pj is the effect of period and eijk is the random error effect.

The animals used in the experiment were 8 local male growing goats. The goats were bought in the area around the Faculty of Agriculture, Nabong campus, Vientiane, Lao PDR. The mean and SD of the initial body weight (BW) of the goats was 15.7 (1.1) kg and the age around 7 months. Before starting the experiment, the goats were treated against parasites with injections of Ivermectin solution (1 ml per 4 kg BW) and were vaccinated against Foot and Mouth disease.

Foliage from Erythrina (Erythrina variegata), Fig (Ficus racemosa), Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus), Jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill), Kapok (Ceiba pentandra) and Mango (Mangifera indica) was hung in separate bunches in a large pen. All foliages were offered in the same amount, 1.5% of the BW as dry matter (DM) and together offered in a total amount of 9 % of the BW. The goats were fed 3 times per day at 08:00 h, 11:00 h and 14:00 h. One goat was let in to the pen every morning and the feeding behaviour was recorded as the time spent consuming each foliage during the day from 08:00 h to 17:00 h. The foliages offered were separated and weighed to estimate the average proportion of leaves plus petioles and stems four times during the experiment and the refusals were also separated into leaves plus petioles and stem every day after feeding. The bunches of foliage were weighed before and after feeding to estimate feed intake from leaves plus petioles and stem of the different species. Fresh bunches of feed and a new goat was provided every day and the procedure was repeated for 8 days.

The data from the preference test is presented in the form of frequencies and means using the Excel program.

The chemical composition of leaves plus petioles and stem of the foliages is presented in Table 1. The Erythrina foliage had a DM content of 197 g and 198 g/kg and a concentration of CP of 193 g and 89 g/kg DM of leaves plus petioles and stem, respectively. The Mango foliage had a CP content of 69 g and 47 g/kg DM and a DM content of 459 g and 352 g/kg of leaves plus petioles and stem, respectively. The other foliages were intermediate between Erythrina and Mango. The content of condensed tannins of leaves plus petioles ranged from 51 g/kg DM in the Erythrina foliage to 130 g/kg DM in the Jackfruit foliage. In Fig and Mango the content of condensed tannins was higher in the stem than in the leaves and petioles while it was lower in Erythrina, Jackfruit, Jujube and Kapok.

|

Table 1. Chemical composition and relation between stem and leaves of the foliages1 |

||||||

|

|

Erythrina |

Fig |

Jackfruit |

Jujube |

Kapok |

Mango |

|

Number of samples |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

Fresh, g/kg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leaves + petioles |

783(110.6) |

676(81.5) |

674(46.1) |

752(53.1) |

712(85.9) |

722(42.2) |

|

Stem |

217(110.6) |

324(81.5) |

326(46.1) |

248(53.1) |

288(85.9) |

278(42.2) |

|

As DM, g/kg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leaves + petioles |

785(105.3) |

725(48.2) |

688 (53.4) |

736(56.9) |

761(69.7) |

775(37.8) |

|

Stem |

215(105.3) |

275(48.2) |

312(53.4) |

264(56.9) |

239(69.7) |

225(37.8) |

|

In leaves + petioles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DM, g/kg |

197(18.2) |

289(60.7) |

327(52.3) |

347(53.3) |

300(36.6) |

459(56.8) |

|

In g/kg DM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CP |

193(35.4) |

119(25.2) |

114(16.3) |

94(21.6) |

120(28.8) |

69(10.6) |

|

NDF |

463(48.2) |

489(38.2) |

461(33.4) |

451(43.9) |

502(45.6) |

501(17.7) |

|

OM |

898(11.9) |

847(37.6) |

901(46.1) |

930(13.4) |

894(27.3) |

940(17.7) |

|

CT |

51(14.3) |

102(21.4) |

130(49.9) |

117(1.7) |

117(4.1) |

90(18.9) |

|

In stem |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DM, g/kg |

198(37.3) |

236(62.7) |

309(64.8) |

375(41.7) |

231(28.4) |

352(90.9) |

|

In g/kg DM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CP |

89(21.9) |

63(14.2) |

62(13.7) |

56(13.9) |

57(17.1) |

47(10.6) |

|

NDF |

525(40.4) |

461(34.8) |

548(37.1) |

571(33.1) |

554(27.0) |

569(35.0) |

|

OM |

906(9.7) |

912(26.9) |

876(20.7) |

958(6.7) |

885(49.8) |

942(17.7) |

|

CT |

51(20.9) |

116(1.8) |

110(9.0) |

100(18.6) |

74(28.6) |

112(6.0) |

| 1 Mean and standard deviation (SD) CT= Condensed tannins | ||||||

Feed offered and feed intake for the six foliages are shown in Table 2. Total DM offered of Jackfruit foliage (965 g DM) was significantly higher than for Erythrina, Fig, Jujube and Mango foliage, but similar to DM offer of Kapok foliage. The total DM intake of Jujube and Mango foliage was lowest, 380 g and 393 g, respectively, significantly different from Jackfruit (with the highest intake of 650 g), Erythrina, and Kapok foliage, but similar to the intake of Fig foliage. Feed intake expressed in percent of BW varied from 2.5% to 4.4%, the highest for Jackfruit and lowest for Jujube.

| Table 2. Feed offered and feed intake1 | |||||||

|

|

Erythrina |

Fig |

Jackfruit |

Jujube |

Kapok |

Mango |

SE |

|

Feed offered, g fresh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leaves + petioles |

3123a |

1856bc |

2064b |

1452c |

2157b |

1216c |

137.0 |

|

Stem |

865a |

870a |

983a |

476b |

867a |

475b |

63.4 |

|

Total |

3988a |

2726b |

3048b |

1929c |

3024b |

1691c |

141.6 |

|

Feed offered, g DM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leaves + petioles |

617ab |

534ab |

662a |

501b |

639ab |

560ab |

33.5 |

|

Stem |

164b |

201b |

303a |

180b |

200b |

171b |

17.9 |

|

Total |

781b |

734b |

965a |

681b |

838ab |

731b |

39.5 |

|

Feed intake, g DM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leaves + petioles |

516a |

428ab |

558a |

316b |

536a |

331b |

34.2 |

|

Stem |

97 |

58 |

92 |

64 |

73 |

62 |

14.8 |

|

Total |

613ab |

485bc |

650a |

380c |

609ab |

393c |

37.6 |

|

Feed intake in % of feed offered |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leaves + petioles |

84a |

80ab |

85a |

63bc |

85a |

57c |

4.4 |

|

Stem |

57a |

30b |

30b |

34ab |

37ab |

34ab |

5.9 |

|

Total |

79a |

66ab |

68ab |

56bc |

73ab |

51c |

3.4 |

|

Feed intake in % of BW |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leaves + petioles |

3.4a |

2.9ab |

3.8a |

2.1b |

3.3a |

2.2b |

0.2 |

|

Stem |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.1 |

|

Total |

4.0ab |

3.4bc |

4.4a |

2.5c |

3.8ab |

2.7c |

0.2 |

|

Water intake, g/day |

94 |

195 |

201 |

194 |

142 |

192 |

49.2 |

|

a,b,cMeans within rows with different superscripts differ significantly (P<0.05) 1 Least squares means and standard error of means |

|||||||

Water intake varied from 94 g 201 g/day, but was not significantly different among foliages. Feeding Erythrina foliage resulted in significantly higher CP intake, 109 g/day, compared to the other foliages (Table 3). The lowest CP intake was obtained with Mango foliage, 25 g/day.

| Table 3. Nutrient intake, digestibility and N retention1 | |||||||

|

|

Erythrina |

Fig |

Jackfruit |

Jujube |

Kapok |

Mango |

SE |

|

Nutrient intake, g/d |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From leaves + petioles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CP |

100a |

51b |

64b |

30c |

65b |

22c |

4.3 |

|

NDF |

240ab |

207ab |

257a |

141bc |

269a |

165bc |

16.8 |

|

OM |

463ab |

365b |

503a |

294bc |

479a |

312bc |

31.5 |

|

From stem |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CP |

9a |

4b |

5ab |

4b |

4b |

3b |

0.9 |

|

NDF |

51 |

30 |

50 |

37 |

40 |

35 |

8.4 |

|

OM |

88 |

53 |

80 |

62 |

65 |

58 |

13.7 |

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CP |

109a |

55b |

69b |

34c |

69b |

25c |

4.2 |

|

NDF |

291ab |

238ab |

307a |

179bc |

309a |

200bc |

19.5 |

|

OM |

551ab |

418b |

583a |

356bc |

543a |

370bc |

35.2 |

|

Digestibility, g/kg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DM |

615a |

466b |

514ab |

527ab |

572ab |

486ab |

31.9 |

|

CP |

731a |

238c |

542ab |

387bc |

660a |

248c |

54.0 |

|

NDF |

542a |

319b |

394ab |

336b |

505a |

341b |

40.3 |

|

OM |

641a |

500b |

569ab |

556ab |

600ab |

519ab |

30.7 |

|

N-retention, g/day |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

N in feed |

17.4a |

8.8b |

11.1b |

5.4c |

11.0b |

4.0c |

0.7 |

|

N in faeces |

4.7abc |

6.3a |

5.1ab |

3.1c |

3.6bc |

2.9c |

0.4 |

|

N in urine |

8.6a |

1.1c |

3.2b |

1.1c |

3.9b |

0.6c |

0.4 |

|

N retention |

4.1a |

1.4bc |

2.9ab |

1.1c |

3.5a |

0.5c |

0.4 |

|

a,b,cMeans within rows with different superscripts differ significantly (P<0.05) 1Least squares means and standard error of means |

|||||||

The DM digestibility, the nutrient digestibility (OM, NDF or CP) and the N retention were generally significantly higher for Erythrina, Jackfruit and Kapok foliage than for Fig, Jujube and Mango foliage.

| Table 4. Live weight and weight changes during the digestibility experiment (Least squares means and standard error of means) | |||||||

|

|

Erythrina |

Fig |

Jackfruit |

Jujube |

Kapok |

Mango |

SE |

|

Weight at start, kg |

15.0 |

14.5 |

14.7 |

15.2 |

15.9 |

14.2 |

0.5 |

|

Weight change, g/day |

78.6 |

16.7 |

85.7 |

9.5 |

57.1 |

-26.2 |

41.2 |

The changes in live weight throughout the experiment ranged from a negative value (-26.2 g/day) for the Mango foliage to 85.7 g/day for the Jackfruit foliage (Table 4). However, there were no significant differences among the six foliages.

The DM content of leaves plus petioles and stem ranged from 86 g and 47 g/kg in the water spinach to 446 g and 352 g/kg in the Mango foliage (Table 5). The CP content in water spinach was high, 249 g and 126 g/kg DM, for leaves plus petioles and stem, respectively.

| Table 5. Chemical composition and relation between stem and leaves of the foliages (Mean and standard deviation) | ||||

|

|

Water spinach |

Fig |

Jujube |

Mango |

|

Number of samples |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

|

Fresh, g/kg |

|

|

|

|

|

Leaves + petioles |

391 (51.7) |

630 (116.3) |

646 (109.4) |

688 (56.5) |

|

Stem |

609 (51.7) |

370 (116.3) |

354 (109.4) |

313 (56.5) |

|

As DM, g/kg |

|

|

|

|

|

Leaves +petioles |

547 (87.2) |

690 (107.0) |

654 (135.8) |

736 (65.9) |

|

Stem |

454 (87.2) |

310 (107.0) |

346 (135.8) |

265 (65.9) |

|

In leaves+ petioles |

|

|

|

|

|

DM, g/kg |

86 (6.0) |

276 (59.3) |

330 (54.7) |

446 (39.2) |

|

In g/kg DM |

|

|

|

|

|

CP |

249 (19.3) |

131 (21.7) |

137 (24.3) |

87 (14.1) |

|

NDF |

448 (23.6) |

471 (50.3) |

491 (29.8) |

428 (40.1) |

|

OM |

826 (33.0) |

847 (24.6) |

936 (26.7) |

935 (29.0) |

|

In stem |

|

|

|

|

|

DM, g/kg |

47 (12.5) |

215 (69.8) |

320 (70.1) |

352 (63.6) |

|

In g/kg DM |

|

|

|

|

|

CP |

126 (10.6) |

76 (15.7) |

76 (21.1) |

69 (5.5) |

|

NDF |

398 (22.5) |

519 (58.7) |

579 (39.1) |

488 (38.6) |

|

OM |

797 (36.2) |

919 (25.8) |

963 (14.9) |

949 (22.1) |

Amount of DM offered was not significantly different among the diets JWS, MWS and FWS (757 g, 716 g and 692 g, respectively) but was significantly higher than for the water spinach alone, 336 g (Table 6).

| Table 6. Mean values for feed offered and feed intake1 | |||||

|

|

WS |

FWS |

JWS |

MWS |

SE |

|

Feed offered, g fresh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Foliage |

0 |

2500a |

2148ab |

1600b |

128.2 |

|

Water spinach |

5428a |

945b |

993b |

924b |

61.0 |

|

Total |

5428a |

3445b |

3140bc |

2524c |

155.0 |

|

Feed offered, g DM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Foliage |

0 |

633 |

696 |

659 |

58.2 |

|

Water spinach |

336a |

59b |

61b |

57b |

4.7 |

|

Total |

336b |

692a |

757a |

716a |

58.0 |

|

Feed intake, g DM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Foliage |

0 |

444 |

461 |

399 |

39.4 |

|

Water spinach |

246a |

57b |

44b |

52b |

6.0 |

|

Total |

246b |

501a |

505a |

451a |

40.5 |

|

Feed intake in % of feed offered |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Foliage |

0 |

69 |

68 |

61 |

2.2 |

|

Water spinach |

73b |

97a |

72b |

91a |

2.6 |

|

Total |

73a |

72a |

68ab |

63b |

1.3 |

|

Feed intake in % of BW |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Foliage |

0 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

3 |

0.2 |

|

Water spinach |

2.0a |

0.4b |

0.3b |

0.4b |

0.02 |

|

Total |

2.0b |

3.7a |

3.6a |

3.4a |

0.2 |

|

Water intake, g/day |

31 |

114 |

29 |

36 |

21.2 |

|

a,b,cMeans within rows with different letters differ significantly (P<0.05) 1 Least squares means and standard error of means WS: Water spinach ad libitum FWS: Fig ad libitum + 0.5 % BW as DM of water spinach JWS: Jujube ad libitum + 0.5 % BW as DM of water spinach MWS: Mango ad libitum + 0.5 % BW as DM of water spinach |

|||||

The total feed intake was lowest for the water spinach diet (246 g), which was significantly lower than for the JWS, FWS and MWS diets (505 g, 501 g and 451 g, respectively). However, the water spinach diet had the highest DM intake in % of feed offered (73 %). Feed intake expressed in percent of BW varied from 2% for water spinach as a sole feed and 3.7% for the FWS diet, but there were no significant differences among the three mixed diets. There was no significant difference in water intake among treatments.

|

Table 7. Mean values for nutrient intake, apparent digestibility and N retention1 |

|||||

|

|

WS |

FWS |

JWS |

MWS |

SE |

|

Nutrient intake, g/d |

|

|

|

|

|

|

From foliage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

CP |

0 |

54a |

58a |

33b |

3.6 |

|

NDF |

0 |

211 |

235 |

173 |

18.1 |

|

OM |

0 |

360 |

410 |

343 |

35.0 |

|

From water spinach |

|

|

|

|

|

|

CP |

48a |

11b |

8b |

10b |

1.7 |

|

NDF |

105a |

24b |

19b |

22b |

3.0 |

|

OM |

201a |

46b |

36b |

43b |

5.9 |

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

CP |

48ab |

65a |

66a |

43b |

4.1 |

|

NDF |

105b |

235a |

254a |

195ab |

18.9 |

|

OM |

201b |

406a |

445a |

385a |

38.1 |

|

Apparent digestibility, g/kg |

|

|

|||

|

DM |

762a |

611b |

644ab |

624ab |

29.5 |

|

CP |

794a |

441b |

575b |

547b |

41.1 |

|

NDF |

717a |

464b |

513ab |

440b |

45.3 |

|

OM |

774 |

612 |

639 |

604 |

36.5 |

|

N balance, g/day |

|

|

|

|

|

|

N in feed |

7.7ab |

10.5a |

10.6a |

6.9b |

0.6 |

|

N in faeces |

1.6b |

5.8a |

4.4ab |

3.1b |

0.6 |

|

N in urine |

4.1a |

1.7b |

3.0ab |

1.8b |

0.3 |

|

N retention |

2.0 |

2.9 |

3.1 |

2.1 |

0.3 |

|

a,b,cMeans within rows with different letters differ significantly (P<0.05) 1 Least squares means and standard error of means WS: Water spinach ad libitum FWS: Fig ad libitum + 0.5 % BW as DM of water spinach JWS: Jujube ad libitum + 0.5 % BW as DM of water spinach MWS: Mango ad libitum + 0.5 % BW as DM of water spinach |

|||||

The CP intake in the JWS diet was highest (66 g), significantly different from the water spinach diet (48 g) and the MWS diet (43 g) but similar to the FWS diet (65 g) (Table 7). Both OM and NDF intake from water spinach as a sole feed were significantly lower than for the JWS, FWS and MWS diets. The apparent digestibility of DM, CP and NDF of the water spinach diet was significantly higher compared to the other diets. There were no significant differences in the digestibility of OM, and all diets resulted in a positive N retention, ranging from 2.0 g to 3.1 g per day.

| Table 8. Live weight and weight changes during the digestibility experiment1 | |||||

|

|

WS |

FWS |

JWS |

MWS |

SE |

|

Weight at start, kg |

12.2b |

13.7ab |

14.2a |

13.3ab |

0.3 |

|

Weight change, g/day |

20 |

40 |

50 |

30 |

52.0 |

|

a,b,cMeans within rows with different letters differ significantly (P<0.05) 1 Least squares means and standard error of means WS: Water spinach ad libitum FWS: Fig ad libitum + 0.5 % BW as DM of water spinach JWS: Jujube ad libitum + 0.5 % BW as DM of water spinach MWS: Mango ad libitum + 0.5 % BW as DM of water spinach |

|||||

There were no significant differences among treatments in live weight gain (Table 8).

The time spent eating during the observation day varied between 178 and 390 minutes, with an average and SD of 260 (60.8) minutes (Figure 1). On average 48 (11.3) % of the observation day of 9 hours was spent eating. There was also a large variation in time spent eating the different foliages e.g. for Mango from 3 minutes to 38 minutes and for Jujube from 17 minutes to 114 minutes. More time was in general spent on Erythrina, Jackfruit and Kapok than on Fig, Jujube and Mango.

|

|

|

|

Figure 1. Time in minutes spent eating each foliage during the observation day (9 h) |

Figure 2. The number of times per day the animals changed from one foliage to another |

The number of times per observation day the animals changed from one foliage to another ranged from 83 to 207 times (Figure 2) with an average of 132 (47.7) times per day. In Figure 3 is an example of how many minutes were spent on each foliage. The figure shows animal number 1, the animal with the lowest number of changes and quite short eating time. Animal number 1 spent close to 4 hours eating during the 9 hours of observation compared to animal 5, that spent 6.5 hours. Animal number 1 selected the Mango foliage only twice and 3 minutes were spent eating the Mango foliage while Erythrina, Fig, Jackfruit and Kapok were selected 14 to 22 times.

|

|

|

Figure 3. Time spent in minutes and order when selecting the different foliage species during one observation day (9 h). Animal number 1, the goat with the lowest number of changes (83) from one foliage to another |

The highest DM intake was 809 g/day and the lowest 487 g/day with a mean of 624 (122) g per day (Figure 4). The total intake was on average 4.0 (1.0) % of BW. The DM intake of the different foliage species ranged from 53 g in the Mango foliage to 141 g in the Erythrina foliage (Figure 5). The DM intake expressed in percent of BW (Figure 6) varied from 0.3% to 0.9 %, with the lowest value for Mango foliage and highest for Erythrina.

|

|

|

Figure 4. Intake of different foliages, g DM/observation day (9 h) |

|

| Figure 5. Intake of different foliages, g DM/observation day (9 h) |

The intake of stem (Figure 6) was highest in Jackfruit and lowest in Mango.

|

| Figure 6. Intake of leaves, petioles and stem of the different foliages, g DM/observation day |

The total DM intake (Figure 7) was significantly related to eating time (P=0.002, R2=0.93); the longer the eating time the higher the feed intake. The number of changes from one species to another (Figure 8) was also significantly related to the eating time (P=0.0017, R2=0.80); the longer the eating time the higher the number of changes from one foliage to another.

|

|

|

|

Figure 7. The relation between DM intake, g and eating time, minutes |

Figure 8. The relation between eating time, minutes and number of changes between foliages |

The foliage from Erythrina had a high CP content. This is probably due to the fact that Erythrina is the only one of the studied plants that belongs to the Leguminosae family and consequently has the ability to fix nitrogen. Many authors have found that Erythrina has a high CP content compared to other foliages e.g. Acacia, Fig, Jackfruit, Gliricidia, Leucaena, Mango, Sesbania and Tamarind (Kibria et al 1994; Baidya et al 1995; Simbaya.002; Aregheore and Perera.004; Gregorio et al 2005). However, the results reported on CP content in the Erythrina leaves (205 g to 258 g/kg DM) are higher than the value from this study (193 g/kg DM). This could possibly be due to different ages of the trees or the shoots, the season for collecting samples or different varieties. Erythrina also had a low content of DM, while Mango had a very high content of DM.

The content of condensed tannins in Jackfruit leaves plus petioles was 130 g/kg DM, higher than the 36 g/kg DM of total tannins recorded by Mui et al (2001) and 51 g/kg DM of total tannins obtained by Van et al (2005). The methods of analysis are different, but total tannins should be the same or higher than condensed tannins, which are only one fraction of the total tannins. The way the samples are treated before analysis is very important e.g. drying at a temperature higher than 45oC will result in lower tannin values, since the tannins will be strongly bound to protein and fibre (Palmer et al 2000). However, Mui et al (2001) and Van et al (2005) also showed that the Jackfruit foliage had a higher content of tannins than other foliages and that the tannin content of the leaves was higher than in the stems, which is in agreement with the present study.

The foliages showing the best intake characteristics in total intake as well as feed intake in % of BW were Erythrina, Jackfruit and Kapok. There was nothing in the analysed chemical components except for the low CP content and high DM content of Mango that differed to any great degree between these foliages and the three foliages with inferior intake characteristics, Mango, Jujube and Fig. The tannin content was highest in Jackfruit and Jujube and not very high in Mango and did not seem be a determining factor for feed intake. The DM intake of Mango was lowest of all foliages, at 2.7% of BW. Kibria et al. (1994) also found a low intake of Mango leaves (2.9% of BW) in Black Bengal goats. The differences in feed intake can be due to other factors e.g. structure of the leaves, soft versus hard, and smooth versus waxy or hairy, content of substances causing the foliages to smell or taste distinctly, or morphology of the plants resulting in different bite sizes (Van.006).

The highest DM and CP digestibility and N retention were obtained when feeding Erythrina, Jackfruit and Kapok foliage. These results are supported by Kibria et al. (1994), Baidya et al. (1995), Mui et al. (2002), Nguyen Kim Lin et al (2003), Aregheore and Perera (2004), Van et al. (2005) and Phengvilysouk and Kaensombath (2006). The digestibility of DM did not seem to be closely related to tannin content, and McSweeney et al. (1999) also found that tannin content was poorly correlated with digestibility of DM and N in foliages from some Leucaena varieties and Calliandra. The requirement for a goat weighing 15 kg and growing at 75 g/day is 79 g CP or 50 g digestible CP according to Mandal et al. (2005). This means that the consumption of Erythrina, Jackfruit and Kapok covered the CP requirements of the goats while the other foliages did not. When considering the high digestibility of CP in Erythrina the goats consumed 160% of the requirement of digestible CP. Probably there was a lack of energy that prevented the goats from growing faster in spite of the fact that there was CP available but they could also have reached their genetic capacity for growth. According to Phengvichith (2007) local goats from Laos offered a diet high in energy and protein and dewormed gained 92 g/day. However, care should be taken not to draw any consistent conclusions about growth rate, since the period of feeding each foliage was too short for a proper evaluation.

The leaves plus petioles and stem of water spinach had a higher CP content (249 g and 126 g/kg DM, respectively) compared to Fig, Jujube and Mango foliage. The CP levels were similar to the results of Pathoummalangsy and Preston (2006) and Chiv Phiny and Kaensombath Lampheuy (2006), but lower than the values 262 g to 278 g/kg DM of leaves plus petioles reported by Peng Buntha and Chhay Ty (2006) and Pok Samkol et al. (2006). The higher CP levels reported by these authors can be due to harvesting age of the water spinach or nutrients available in the soil e.g. through supply of fertilizer. The water spinach also had a low DM content, which has also been noted by other authors (Peng Buntha and Chhay Ty.2006; Nguyen Van Hiep and Preston.2006; Khuc Thi Hue and Preston.2006; Pathoummalangsy and Preston.2006; Chiv Phiny and Lampheuy Kaensombath 2006; Pok Samkol et al 2006)

When comparing feed intake for the different diets in Experiment 2 the total feed intake of water spinach was lowest (246 g DM or 2.0% of BW). Buntha and Ty (2006), also found that the DM intake was lower for water spinach (2.2% of BW) compared to Guinea grass and Stylo. However, the intake of CP from water spinach as a sole feed was not significantly different from any of the other diets. Water spinach also had significantly higher DM, CP and NDF digestibility than the other diets

The feed intake, apparent digestibility, N retention and the live weight changes on Fig, Jujube and Mango foliage were improved when the foliages were supplemented with water spinach, compared to the results in Experiment 1 (Tables 2, 3 and 4). Pathoummalangsy and Preston (2006) also found that feed intake and digestibility increased to double the overall values, when supplementing the cassava foliage with water spinach (2% of BW), compared to feeding cassava alone. This can be due to the increased level of protein in the gut if the proteins in the water spinach form complexes with the condensed tannins in the foliages (Reed et al. 1982).

Experiment 3: Time spent selecting different foliage species

The total time spent eating throughout the observation day ranged from 178 to 390 minutes. Theng Kouch et al (2003) found that the eating time was 308 min in 24 h; Keskin et al. (2005) reported an eating time of 383 minutes in 24 h and Van et al. (2005), 255 minutes in 24 h. The average time spent eating in the present study was 48 % of the 9 observation hours, higher than Theng Kouch et al (2003), Samkol (2003) and Keskin et al. (2005), who recorded 21.4 % of 24 h, 35.2 % of 10 h and 26.6 % of 24 hours, respectively. The difference is probably due to the fact that the goats eat mostly during the daytime (Van et al 2005) while they ruminate or sleep in the night time. The period used for recording eating time will thus affect the proportion of time used for eating.

The goats spent most of their eating time on Erythrina, Jackfruit and Kapok, foliages, obviously having the best intake characteristics of the six foliages compared. These three foliages also had the highest crude protein content and digestibility which confirms the opinion of several authors that goats choose and consume the most nutritious feed available (Van Soest 1982; Fajemisin et al 1996). However, the goats also spent quite a long time (114 minutes, more than 40% of the total eating time) on the lower quality foliages. Even though intake of e.g. Jujube was not very high it has been shown that the foliages from the Ziziphus family are preferred by goats (Ngwa et al 2000).

The number of times the goats changed from one foliage to another, and total time spent eating, ranged from 83 to 207 times and 4.0 to 6.5 h, respectively. It seems that eating time and way of selection are highly individual characteristics and can vary within quite a wide range. This has also been noted by among others Morand-Fehr et al. (1991) and Abijaoude et al. (2000), who found that the eating time of goats varied between 4 h and 9 h per day.

In general the behaviour study confirmed earlier studies that goats prefer to select and consume many different types of foliage every day (Sanon et al 2007) and will do so even if the nutrient quality of some of the foliages is not high.

The mean DM intake per observation day was lower, 624 g and 4.0% of BW, compared to the 4.2% to 4.8% of BW obtained by Theng Kouch et al (2003) and Van et al. (2005), respectively, when using the hanging method feeding Jackfruit, Mulberry and Cassava foliage. Hanging seems to be the best way to improve feed intake and eating rate of goats, especially when the foliages have low intake characteristics (Theng Kouch et al 2003; Pok Samkol 2003; Van et al 2005; Phengvilaysouk and Kaensombath.Lampheuy 2006), although intake will also depend on foliage species available. When the goats have many species to choose between they will obviously not only select the foliages with the best quality but also eat small amounts of other foliages, as discussed above, and this will result in lower intake. In the case of Van et al. (2005) Jackfruit was the only foliage available. The low DM intake of Mango foliage, 53 g or 0.3% of BW, compared to the other foliages, is probably due to the structure of the leaves. The leaves of Mango are hard and have a high DM content and the goats preferred the petioles to the leaves and stems of Mango. The Erythrina foliage had a soft and smooth structure in all parts (leaves, petioles and stem) and this could have contributed to the higher intake of Erythrina, as also suggested by Aregheore and Perera (2004).

The proportion of leaves plus petioles and stem of foliage can also have affected the intake. Fig, Jujube and Mango foliages had a higher percentage of stem with a hard structure compared to Erythrina, Jackfruit and Kapok foliages. The highest feed intake was from the three foliages which had a high proportion of leaves plus petioles. Goats generally prefer to select shoots, leaves and stem in that order (Steele, 1996).

There was a close relation between total DM intake and eating time, and also eating time and number of times the goats changed foliage species, respectively. This resulted in a mean eating rate, of 2.5 g per minute compared to 1.1 g per minute obtained by Samkol (2003) and 3.5 g per minute recorded by Theng Kouch et al (2003). Differences in eating rate can be due to individual characteristics as well as type of feed, methods of presenting the feed etc.

ˇ The Erythrina, Jackfruit and Kapok foliages had better intake characteristics, CP digestibility and N retention than Fig, Jujube and Mango foliages.

ˇ However, there were large individual differences concerning preferred foliage species, eating rate and selective behaviour.

ˇ Water spinach can be used as a supplement to the foliages of lower quality to increase DM and CP intake, apparent digestibility and N retention.

ˇ Of the foliage species studied, Erythrina especially, but also Kapok, seem to be interesting species, on which little research, at least when used as a feed for goats, has been done.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Swedish International Development Agency/ Department for Research Cooperation with Developing Countries (Sida/SAREC) for financial support of this research, the Faculty of Agriculture, National University of Laos for making the facilities available and the four students of HD3 (12th Generation) in this institution for taking care of the goats. Thanks are also due to Dr. Xe for statistical advice.

Ajayi D A, Adeneye J A and Ajayi F T 2005 Intake and nutrient utilization of West African

Dwarf Goats fed Mango (Mangifera indica), Ficus (Ficus thionningii), Gliricidia (Gliricidia

sepium) foliages and concentrates as supplements to a basal diet of Guinea grass (Panicum maximum). World Journal of Agricultural Sciences 1, 184-189.

AOAC 1990 Association of Official Analytical Chemists Official methods of analysis. 15th Edition. Arlington, Virginia.

Aregheore E M and Perera D 2004 Effects of Erythrina variegata, Gliricidia sepium and Leucaena leucocephala on dry matter intake and nutrient digestibility of maize stover, before and after spraying with molasses. Animal Feed Science and Technology 111, 191-201.

Chhay Ty and Preston T R 2005: Effect of water spinach and fresh cassava leaves on growth performance of pigs fed a basal diet of broken rice. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 17, Article #76. Retrieved July 13, 2005, from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd17/7/chha17076.htm

Chen X B and Gomes M J 1992 Estimation of microbial protein supply to sheep and cattle based on urinary excretion of purine derivatives – an overview of the technical details. An occasional publication of the Rowett Research Institute,Greenburn Road, Bucksburn, Aberdeen, AB2 95B, UK.

Chiv Phiny and Lampheuy Kaensombath 2006:

Effect on feed intake and growth of depriving rabbits access to

caecotrophes. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 18, Article

#34. Retrieved June 8, 2007, from

http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd18/3/phin18034.htm

Goering H and Van Soest P 1970 Forage fiber analysis. Agricuture hand book No. 379. United States Department of Agriculture, Washington D.C, USA.

Gregorio E, Carlos A and Concepción M 2005 Defaunating capacity of tropical fodder trees: Effect of polyethylene glycol and its relationship to in vitro gas production. Animal Feed Science and Technology. Abstract 1, 313-327.

Keskin M, Sahin A, Bicer O, Gul S, Kaya S, Sari A and Duru M 2005 Feeding Behaviour of Awassi Sheep and Shami (Damascus) Goats. Turkish Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences 29: 435-439

Kibria S S, Vahar T N and Mia M M 1994 Tree leaves as alternative feed resource for Black Bengal goats under stall-fed conditions. Small Ruminant Research 13, 217-222.

Khuc Thi Hue and Preston T R 2006: Effect of different sources of supplementary fibre on growth of rabbits fed a basal diet of fresh water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica). Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 18, Article #58. Retrieved June 8, 2007, from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd18/4/hue18058.htm

Makkar H P S, Blummel M and Becker K 1995 Formation of complexes between polyvinily pyrorolidones or polyethylene glycols and their implication in gas production and true digestibility in vitro techniques. British Journal of Nutrition, 73:897-913.

Mandal A B, Paul S S, Mandal G P, Kannan A and Pathak N N 2005 Deriving nutrient requirements of growing Indian goats under tropical condition. Small Ruminant Research 58, 201-217.

McSweeney C S, Palmer B, Bunch R and Krause D O 1999 In vitro quality assessment of tannin-containing tropical shrub legumes: protein and fibre digestion. Animal Feed Science and Technology 82, 227-241.

Minitab 2000 Minitab Reference Manual, Release 13.31 for Windows. Minitab Inc., USA.

Morton J 1987 Indian Jujube. pp. 272-275. http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/morton/index.html

Mui N T, Ledin I, Udén P and Binh D V 2001 Effect of replacing a rice bran-soya bean concentrate with Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) or Flemingia (Flemingia macrophylla) foliage on the performance of growing goats. Livestock Production Science 72, 253-262.

Mui N T, Ledin I, Udén P and Binh D V 2002 Nitrogen balance in goats fed Flemingia (Flemingia macrophylla) and Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) foliage based diets and effect of daily supplementation of polyethylene glycol (PEG) on intake and digestion. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 15:5, 699-707.

Nguyen Kim Lin, Preston T R , Dinh Van Binh and Nguyen Duy Ly 2003: Effects of tree foliages compared with grasses on growth and intestinal nematode infestation in confined goats. Livestock Research for Rural Development 15 (6). http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd15/6/lin156.htm

Nguyen Van Hiep and Preston T R 2006 Effect of cattle manure and biodigester effluent levels on growth and composition of water spinach. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 18, Article #48. Retrieved June 8, 2007, from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd18/4/hiep18048.htm

Nath K, Malik N S and Singh O N 1996 Utilization of Zizyphus nummularia leaves by three breeds of sheep. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 20, 1137-1142.

Nguyen Thi Hong Nhan and Preston T R 1997 Effect of sugar cane juice on milk production of goats fed a basal diet of jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) leaves. Livestock Research for Rural Development (9). http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd9/2/nhan92.htm

Palmer B, Jones R J, Wina E and Tangendjaja B 2000 The effect of sample drying conditions on estimates of condensed tannin and fibre content, dry matter digestibility, nitrogen digestibility and PEG binding of Calliandra calothyrsus. Animal Feed Science Technology 87, 29-40.

Pathoummalangsy Khamparn and Preston T R 2006 Effect of a supplement of fresh water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) on feed intake and digestibility in goats fed a basal diet of cassava foliage. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 18, Article #35. Retrieved April 24, 2007, from

http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd18/3/kham18035.htm

Pheng Buntha and Chhay Ty 2006 Water-extractable dry matter and neutral detergent fibre as indicators of whole tract digestibility in goats fed diets of different nutritive value. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 18, Article No. 33. http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd18/3/bunt18033.htm

Phengsavanh P 2003 Goat production in smallholder farming systems in Lao PDR and the possibilty of improving the diet quality by using Stylosanthes guianensis CIAT 184 and Andropogon gayanus cv Kent. MSc. Thesis. Department of Animal Nutrition and Management, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden.

Phengvichith V 2007 Effect of a diet high in energy and protein on growth, carcass characteristics and parasite resistance in goats. Tropical Animal Health and Production 39, 59-70.

Phengvilaysouk A and Kaensombath Lampheuy 2006 Effect on intake and digestibility by goats given jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) leaves alone, the whole branch or free access to both. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 18, Article No. 38. http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd18/3/amma18038.htm.

Pok Samkol, Preston T R and Ly J 2006: Effect of increasing offer level of water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) on intake, growth and digestibility coefficients of rabbits. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 18, Article #25. Retrieved June 8, 2007, from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd18/2/samk18025.htm

Reed J, Robert D, McDowell E, Van Soest P J and Horvath P J 1982 Condensed Tannins: A factor limiting the use of cassava forage. Journal of Science Food Agriculture 33. pp. 213-220.

Reich L 1991 Uncommon Fruits Worthy of Attention. Reading, Mass., Addision- Wesley. pp. 139-146, from: http://www.crfg.org/fg/xref/xref-J.html#jujube

Schurrie H 1990 The Fig. Timber Press Horticultural Reviews 12, 409.

Simbaya J 2002 Potential of tree fodder/shrub legumes as feed resources for dry season supplementation of smallholder ruminant animals. National Institute for Scientific and Industrial Research, Livestock and Pest Research Centre, Chilanga, Zambia 69-76.

Theng Kouch, Preston T and Ly J 2003: Studies on utilization of trees and shrubs as the sole feedstuff by growing goats; foliage preferences and nutrient utilization. Livestock Research for Rural Development 15 (7). http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd15/7/kouc157.htm

Theng Kouch, Preston T R and Hun Hieak 2006: Effect of supplementation with Kapok (Ceiba pentandra) tree foliage and Ivermectin injection on growth rate and parasite eggs in faeces of grazing goats in farmer households. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 18, Article No. 87. http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd18/6/kouc18087.htm

Van D T T, Mui N T and Ledin I 2005 Tropical foliages: effect of presentation method and species on intake by goats. Animal Feed Science and Technology 118, 1-17.

Van D T T 2006 Some animal and feed factors affecting feed intake, behaviour and performance of small ruminants. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae. Doctoral thesis no 2006:32. SLU, P.O. Box 7024, 750 07 Uppsala, Sweden.