|

|

| Photo 1. Van Pa sow | Photo 2. Van Pa growing pigs |

|

Live stock production, climate change and resource depletion |

Fresh taro leaves and fresh foliage of taro (leaves and stem) were collected 5-6 months after planting and spread out on the floor some hours for wilting, prior to being chopped into small pieces (2 - 3 cm), mixed with 0.5 % salt and molasses at 0 or 4% levels, and sealed in plastic bags with a capacity of 2- 3 kg. In two other treatments, the taro leaves or taro leave plus stems, after chopping were processed by hammer mill and also mixed with 0.5 % salt. On all treatments the pH had fallen to slightly above, or below, 4 by 7 days. The pH values were lower for the mixture of leaves plus stems than leaves alone, except when molasses was added when differences were minimal. There were no advantages in using molasses or hammer-milling when the stems were ensiled together with the leaves.

The 3 experimental diets fed to Van Pa pigs (of about 5 months of age, with an average body weight of 21.6 ± 1.24 kg) were: FM (control diet): protein source fish meal; MTC50: 50 % protein of supplementary protein from fishmeal and 50% from mixture of ensiled taro and ensiled cassava leaves; MTC100: 100 % supplementary protein from mixture of ensiled taro and ensiled cassava leaves. The design was a 3 x 3 Latin Square and the experiment lasted for a total of 30 days. Each of the three experimental periods was 10 days, comprising 5 days of adaptation to each diet followed by 5 days of collection of faeces and urine. The pigs were kept individually in metabolism cages for 30 days familiarize them with new feed and housing before carrying out the experiment. DM feed intake was decreased as the mixed Taro and cassava leaf silages replaced fish meal. Apparent digestibility coefficients for DM, OM and crude protein did not differ among the diets, but N retention was decreased, mainly because of reduced feed intake, and hence of N, as the level of mixed silage was increased.

In Central Vietnam, there are several local (indigenous) pig breeds (Pa Co, Van Kieu and Van Pa. These local breeds readily consume raw green feed high, they withstand harsh climates, and are resistant against certain diseases. The meat is considered to be delicious with comparable taste to that from the wild pigs. Van Pa is one of ithe ndigenous pig breeds that is well adapted to local environmental conditions and is popular with smallholder farmers in upland areas of Central Vietnam (Photos 1 and 2). This local breed of pig has a low growth rate but has good quality of meat. At present, in some provinces of central Vietnam, the farmers in the mountainous areas have been encouraged to develop this local breed.

|

|

| Photo 1. Van Pa sow | Photo 2. Van Pa growing pigs |

Taro (Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott), which originated in India and South East Asia, is presently cultivated in many tropical and subtropical countries. Taro can be a potential protein source for animals, especially pigs due to the good nutritional quality of the leaves (DM basis): 25% crude protein (CP), 12.1% crude fibre (CF), 12.4% Ash, 10.7% ether extract (EE), 39.8% nitrogen-free extract (NFE), 1.74% Ca, and 0.58% P (Göhl 1971). Leterme et al. (2005) reported that Xanthosoma leaf had high amino acid content and a good balance of amino acids.

In Vietnam Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) is the second most important food crop after rice in terms of total production. In 2007 560 thousand ha of cassava were planted (Statistical Yearbook, 2008). Many studies have concluded that cassava leaves can be considered as potentially valuable protein sources for pigs, and can replace fish meal, soybean meal and groundnut cake as a protein source for pigs (Preston 2001, 2006; Khieu Borin et al 2005; Nguyen Thi Hoa Ly 2006; Bui Huy Nhu Phuc et al 2001, Bui Huy Nhu Phuc 2005). Ensiling can be the most appropriate method to preserve taro and cassava leaves and reduce anti-nutritional factors in taro and cassava leaves for feeding animal (Du Thanh Hang and Preston 2005; Man and Wiktorsson 2002; Man et al 2009; Tiep et al 2006).

In Central Vietnam cassava and vegetables such as sweet potato and taro leaves based pig production systems are very common and play an important role in the economics of small farms in uplands.

This study aimed to determine the effects of different levels of various additives and time on the quality of taro silages and to determine the digestibility and nitrogen balance in Van Pa pigs of diets with ensiled mixtures of ensued Taro and ensiled cassava leaves replacing fish meal.

Fresh taro leaves or fresh foliage of taro (leaves and stem) were collected 5- 6 months after planting and spread out on the floor some hours for wilting. The taro leaves or taro foliages were chopped into small pieces (2 - 3 cm), mixed with 0.5 % salt and additive of molasses at 0% or 4% levels, and sealed in plastic bags with a capacity of 2- 3 kg. In two other treatments, the taro leaves or taro foliages after chopping into small pieces (2 - 3 cm), were processed by hammer mill and also mixed with 0.5 % salt.

The 6 treatments were:

T: Taro leaves + 0.5 % NaCl

HT: Same as T but processed by hammer mill after chopping + 0.5 % NaCl

TM: Taro leaves + 4 % molasses + 0.5 % Nacl

TLS: Taro leaves + stem (in portion found in the whole plant) + 0.5 % NaCl

HTS: Same as TLS but processed by hammer mill after chopping + 0.5 % NaCl

TLSM: Taro leaves + stem (in portion found in the whole plant) +4 % molasses + 0.5 % NaCl

The hypothesis to be tested was that in the hammer mill the cells are broken and therefor the sugars are more available.

Samples of silage were taken after 0, 7, 14, 30 and 60 days after ensiling and evaluated by approximate analysis for pH, DM, CP and total ash.

The pH value of the silage was recorded on fresh samples by a pH electrode; Samples for chemical analysis were dried at 60oC for 24 h and ground through a 1 mm screen. The dry matter (DM) was determined by drying at 105oC for 4h to constant weight. The CP (N x 6.25) and ash were determined according to AOAC (1990).

The experiment was carried out at the Hue University research farm from February to April 2009.

Three Van Pa pigs of about 5 months of age, with an average body weight of 21.6 ± 1.24 kg were kept individually in metabolism cages that allowed the separate collection of urine and faeces. The size of the metabolism cages was 1.5 x 0.55 m (length x width) and they were made of galvanized steel with plastic slatted floor. The pigs were vaccinated against pasteurellosis and hog cholera before starting the experiment.

Fresh leaves of cassava were collected at the time of root harvest and spread out on the floor 5 hours for wilting. The leaves were separated from the stems and petioles, chopped into small pieces (2 - 3 cm), mixed with salt (0.5 %) and then ensiled with molasses at 4 % weight of the wilted cassava leaves. The cassava leaf silage was kept in sealed airtight plastic bags with a capacity of 30 kg, and was stored for 1 month prior to feeding. Fresh taro leaves were collected 5- 6 months after planting with subsequent harvests at 15- 20 day intervals and spread out on the floor 15 hours for wilting, chopped into small pieces (2 - 3 cm), mixed with 0.5 % salt and molasses at 4 % weight of wilted taro leaves. The taro leaves silage also was kept in sealed airtight plastic bags with a capacity of 30 kg, and was stored for 14 days prior to feeding.

The 3 experimental diets were fed according to a 3 x 3 Latin Square and the experiment lasted for a total of 30 days. Each of the three experimental periods was 10 days, comprising 5 days of adaptation to each diet followed by 5 days of collection of faeces and urine. The pigs were kept individually in metabolism cages for 30 days familiarize them with new feed and housing before carrying out the experiment.

The diets were: :

The rest of the diets were cassava root meal and rice bran (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Chemical composition of the feed ingredients (% of DM) |

|||||||

|

ME MJ/kg DM |

CP |

EE |

CF |

Ash |

Lys |

Met |

|

|

ETL |

11.8 |

25.1 |

4.5 |

14.8 |

16.4 |

11.2 |

6.7 |

|

ECL |

10.7 |

24.2 |

7.0 |

14.3 |

8.0 |

11.3 |

4.8 |

|

CRM |

13.8 |

3.2 |

2.1 |

3.5 |

1.9 |

1.4 |

0.03 |

|

RB |

11.5 |

10.4 |

11.9 |

9.4 |

9.0 |

5.4 |

2.5 |

|

FM |

11.6 |

48.0 |

5.4 |

- |

29.9 |

22.2 |

8.8 |

|

ETL: ensiled

taro leaves; ECL: ensiled cassava leaves; CRM: cassava root meal; RB:

rice bran; FM: fish meal. |

|||||||

All diets was formulated to contain 100 g CP/kg DM and about 12.5 MJ ME / kg DM (Table 2).

|

Table 2. Proportions of diet ingredients and chemical composition (% in DM) of the experimental diets |

|||

|

|

FM |

MTC50 |

MTC100 |

|

Ingredients, % |

|

|

|

|

Ensiled taro leaves |

- |

4.0 |

8.0 |

|

Ensiled cassava leaves |

- |

4.0 |

8.0 |

|

Fish meal |

8.0 |

4.0 |

- |

|

Cassava root meal |

46.0 |

41.5 |

36.0 |

|

Rice bran |

46.0 |

46.5 |

48.0 |

|

Chemical composition |

|||

|

Organic matter |

92.6 |

92.8 |

93.0 |

|

Crude Protein |

10.0 |

10.0 |

10.0 |

|

Ether extract |

6.9 |

7.1 |

7.4 |

|

Crude fibre |

6.0 |

7.0 |

8.1 |

| Calculated values | |||

|

ME (MJ/kg DM) |

12.6 |

12.4 |

12.3 |

|

Lys (g/kg DM) |

5.0 |

4.9 |

4.9 |

|

Met (g/kg DM) |

1.9 |

2.0 |

2.1 |

|

HCN (mg/kg) |

|

6.4 |

12.8 |

The feeding level during the collection period was set slightly below the maximum level. The pigs were fed two times per day at 7:00 and 16:00 h, with the daily allowance equally divided between the two meals. Food refusals and spillage were recorded, and were used to correct the food intake data.

Feeds and residues was recorded daily during the last 5 days of each period. Faeces and urine were collected daily and stored at - 180C and at the end of each experimental period samples were pooled and mixed. Sub-samples were taken and dried at 600C prior to chemical analysis. Urine was collected in a bucket containing 50 ml of 10% sulphuric acid (H2SO4) to keep the pH below 4 so as to prevent escape of ammonia.

Analyses of variance was performed according to a 3 x 3 Latin-Square design using the General Linear Model (GLM) procedure in the ANOVA rogfram of the Minitab software (Minitab 2000). The Tukey test in the same software was used to test pair-wise comparisons with a confidence level of 95%. Results was presented as Least Squares Means with their pooled standard errors.

On all treatments the pH had fallen to slightly above, or below, 4 by 7 days (Table 3; Figures 1-3). The pH values were lower for the mixture of leaves plus stems than leaves alone, except when molasses was added when differences were minimal. There were no advantages in using molasses or hammer-milling when the stems were ensiled together with the leaves. The advantages of ensiling the combined leaves and stems corroborate the findings of Rodriguez and Preston (2009) and Hoang Nghia Duyet (2011).

|

Table 3. Effect of molasses (M) or hammer-milling (H) and ensiling time on the pH of taro leaves (T) or taro leaves plus stems (TS) |

|||||||

|

|

Ensiling time, days |

||||||

|

0 |

7 |

14 |

30 |

60 |

SEM |

P |

|

|

T |

6.01a |

4.45b |

4.42c |

4.58d |

4.37e |

0.002 |

0.001 |

|

HT |

6.01a |

4.32b |

4.35c |

4.43d |

4.56e |

0.003 |

0.001 |

|

TM |

6.01a |

3.91b |

3.86c |

3.91b |

4.05d |

0.003 |

0.001 |

|

TS |

6.01a |

3.81b |

3.73c |

3.89b |

3.59c |

0.003 |

0.001 |

|

HTS |

6.01a |

3.77b |

3.71c |

3.73c |

3.84d |

0.005 |

0.001 |

|

TSM |

6.01a |

3.72b |

3.73b |

3.58c |

4.55d |

0.004 |

0.001 |

|

SEM: standard

error of mean; P: probability |

|||||||

|

|

| Figure 1: Changes in pH for taro leaves or leaves + stems ensiled with no other treatment | Figure 2: Changes in pH for taro leaves or leaves + stems ensile with 4% molasses |

|

|

| Figure 3: Changes in pH for taro leaves or leaves + stems ensiled after hammer-milling |

There was a slight reduction of about 10% in DM content with ensiling time (Table 4). Notable is the relatively low DM content (range of 9.6 to 13.3% ) f the mixed Taro leaves and stems. Contrat to many recommendations ( minimum 30% of DM to make good silage; McDonald 1981) this did not interfere with the ensiling process; in fact pH was always lower for leaf and stem silages than for ensiled es where the DM content was almost double.

|

Table 4. Effect of molasses (M) or hammer-milling (H), and ensiling time on the DM (%) of ensiled taro leaves (T) or taro leaves plus stems (TS) |

|||||||

|

|

Ensiling time, days |

||||||

|

0 |

7 |

14 |

30 |

60 |

SEM |

P |

|

|

T |

19.71a |

19.84b |

19.95c |

18.35d |

17.14e |

0.023 |

0.001 |

|

HT |

20.11a |

20.25a |

19.45b |

19.04c |

17.40d |

0.032 |

0.001 |

|

TM |

22.21a |

22.08a |

22.29a |

21.49b |

19.60c |

0.047 |

0.001 |

|

TS |

11.98a |

11.85a |

11.14b |

10.62b |

9.66c |

0.142 |

0.001 |

|

HTS |

12.11a |

12.10a |

11.43b |

10.25c |

10.42c |

0.105 |

0.001 |

|

TSM |

13.32a |

13.25ab |

12.91b |

12.12c |

11.56d |

0.073 |

0.001 |

|

SEM: standard

error of mean; P: probability |

|||||||

Crude protein in the silages declined marginally (about 10%) with ensiling time. Ensiling leaves and stems together resulted in crude protein contents in the range 16 to 17% in DM (Table 5). Assuming an average value of 11% crude protein in rice bran then 50:50 mixtures with ensiled Taro leaves and stems would result in a balanced feed with about 14% crude protein.

|

Table 5. Effect of molasses (M) and Hammer-milling (H), and ensiling time, on the crude protein (% in DM) of taro leaves (T) and taro leaves plus stems (TS) |

|||||||

|

|

Ensiling time, days |

||||||

|

0 |

7 |

14 |

30 |

60 |

SEM |

P |

|

|

T |

27.84a |

27.87a |

26.96b |

26.43bc |

26.01c |

0.170 |

0.001 |

|

HT |

27.84a |

27.66a |

26.10b |

26.39b |

25.50b |

0.189 |

0.001 |

|

TM |

26.86a |

26.86a |

25.63b |

25.12c |

24.87d |

0.035 |

0.001 |

|

TS |

17.22a |

17.18a |

16.97a |

16.54b |

15.98c |

0.106 |

0.001 |

|

HTS |

17.07a |

17.07a |

16.65ab |

16.27b |

15.41c |

0.112 |

0.001 |

|

TSM |

16.48a |

16.42ab |

16.05b |

15.74c |

14.98d |

0.084 |

0.001 |

|

SEM: standard

error of mean; P: probability |

|||||||

The ash content in the silages increased slightly with time of ensiling and did not appear to be influenced by the processing method (Table 6). The relatively high values (14 to 18% in DM) suggest that the mixed leaf-stem silage could be an important source of minerals. Data from Gőhl (1971) indicate that the DM of fresh leaves contain 1.74 % calcium and 0,58% phosphorus. Assessment of the bioavailability of these minerals in Taro silage merits research in view of varying levels of oxalate salts in the Taro leaves and stems (Du Thanh Hang et al 2010), which could result in the formation of insoluble calcium oxalate.

|

Table 6. Effect of molasses (M) and Hammer-milling (H), and ensiling time, on the ash content (% in DM) of taro leaves (T) and taro leaves plus stems (TS) |

|||||||

|

|

Ensiling time, days |

||||||

|

0 |

7 |

14 |

30 |

60 |

SM |

P |

|

|

T |

14.47a |

14.82a |

15.00a |

15.56bc |

15.95c |

0.147 |

0.001 |

|

HT |

14.47a |

14.99b |

15.20b |

15.37bc |

15.88c |

0.101 |

0.001 |

|

TM |

15.25a |

15.43a |

15.58ab |

16.27b |

16.42d |

0.154 |

0.001 |

|

TS |

16.04a |

16.02a |

16.12a |

16.63b |

17.16c |

0.093 |

0.001 |

|

HTS |

16.14 |

16.07 |

16.11 |

16.56 |

17.02 |

0.229 |

0.063 |

|

TSM |

16.22a |

16.17a |

16.17a |

16.04b |

17.58c |

0.067 |

0.001 |

|

SEM: standard

error of mean; P: probability |

|||||||

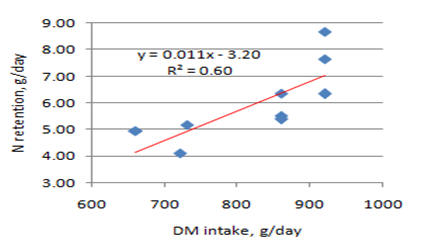

DM feed intake was decreased as the mixed Taro and cassava leaf silages replaced fish meal (Table 7). Apparent digestibility coefficients for DM, OM and crude protein did not differ among the diets, but N retention was decreased, mainly because of reduced feed intake, and hence of N, as the level of mixed silage was increased. It is possible that the ensiled cassava leaves were the major cause of the reduced nutritive value of the diets containing the mixed silages. Manivanh Nouphone and Preston (2011) reported highest intake (50 g DM/kg LW) and N retention (78% of N intake) in growing pigs fed silage of Taro leaves and stems at 50% of the DM of a diet based on rice bran. On a 100% taro silage diet, apparent DM digestibility was 90% and that of crude protein 88%. There are no comparable data for cassava leaf silage, fed at high levels in the diet, but several reports indicate that pig performance is improved when cassava leaf silage (or fresh leaves) are partially or fully replaced by more digestible foliages such as water spinach (Chhay Ty et al 2005a,b; 2006) or duckweed (Nguyen Van Lai and Rodriguez (1998). In thse report, the improvement in prformance as cassva leaves werfe replace bu more nutritios foliages, was mainly the results of highger voluntary feed intake. This appeared t be the case in the presenrt experiument where N retention was linearly related with feed DM intake ( the poorer performance on cassvca leaves

|

Table 7. Mean values of feed intake, apparent digestibility and N balance in growing Van Pa pigs fed cassava root meal and rice bran and increasing proportions (0 to 100%) of dietary protein from a mixture of ensiled taro leaves and cassava leaves (MTC) replacing protein from fish meal (FM) |

|||||

|

|

FM |

MTC50 |

MTC100 |

SEM |

P |

|

DM intake, g/d |

920a |

860b |

703c |

12.6 |

0.001 |

|

Apparent digestibility, % |

|||||

|

DM |

88 |

84 |

84 |

1.75 |

0.406 |

|

OM |

89 |

87 |

87 |

1.32 |

0.483 |

|

CP |

76 |

68 |

69 |

3.45 |

0.266 |

|

N balance, g/d |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intake |

14.7a |

13.8b |

11.3c |

0.202 |

0.001 |

|

Faeces |

3.5 |

4.5 |

3.5 |

0.483 |

0.333 |

|

Urine |

3.6 |

3.6 |

3.1 |

0.267 |

0.312 |

|

Retained |

7.6a |

5.8ab |

4.8b |

0.470 |

0.015 |

|

N retained/N Intake, % |

51 |

42 |

42 |

3.54 |

0.183 |

|

N retained/ N digested, % |

67 |

62 |

61 |

2.73 |

0.283 |

|

abc mean

values within rows without common letter are different at P < 0.05 |

|||||

|

| Figure 4: Relationship between DM intake and N retention in pigs fed increasing proportions of taro leaf silage and cassava leaf silage replacing fish meal |

AOAC 1990 Official methods of analysis. Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Arlington, Virginia, 15thedition.

Chhay Ty Borin K Preston T R and Mea Sokveasna 2007 Intake, digestibility and N retention by growing pigs fed ensiled or dried Taro (Colocasia esculenta) leaves as the protein supplement in basal diets of rice bran/broken rice or rice bran/cassava root meal. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 19, Article #137. http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd19/9/chha19137.htm

Chhay Ty and Preston T R 2005a Effect of water spinach and fresh cassava leaves on intake, digestibility and N retention in growing pigs. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Vol. 17, Art. No. 23. http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd17/2/chha17023.htm

Chhay Ty and Preston T R 2005b Effect of water spinach and fresh cassava leaves on growth performance of pigs fed a basal diet of broken rice. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 17, Article No. 76. http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd17/7/chha17076.htm

Chhay Ty and Preston T R 2006 Effect of different ratios of water spinach and fresh cassava leaves on growth of pigs fed basal diets of broken rice or mixture of rice bran and cassava root meal. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 18, Article No. 57. http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd18/4/chha18057.htm

Bui Huy Nhu Phuc, Ogle R B and Lindberg J E 2001 Nutritive value of cassava leaves formomogastric animal. Proceeding International Workshop "Current Research and Development on Use Of Cassava as Animal Feed" held in Khon Kaen University, Thailand. July 23- 24, 2001. http://www.mekarn.org/procKK/phuc.htm

Bui Huy Nhu Phuc 2005.Effects of cassava leaves on the performance of growing pigs. Paper presented at Regional seminar-workshop on " Sustainable Livestock Based Agriculture in the Lower Mekong Basin". Organized and Sponsored by Cantho Uni. and MEKARN Programme held in Can Tho University, Vietnam. May 23-25, 2005.

Du Thanh Hang and Preston T R 2005 The effects of simple processing methods of cassava leaves on HCN content and intake by growing pigs. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 17, Article No. 99. http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd17/9/hang17099.htm

Du Thanh Hang and Preston T R 2010 Effect of processing Taro leaves on oxalate concentrations and using the ensiled leaves as a protein source in pig diets in central Vietnam. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 22, Article #68. http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd22/4/hang22068.htm

Göhl B 1971 Animal Production and Health Division, FAO, 00100-Rome, Italy. Database program (Speedy A W and Waltham N 2008)http://www.fao.org/ag/AGA/AGAP/FRG/afris/default.htm

Hoang Nghia Duyet 2010 Ensiled taro foliage (leaves + stems) as replacement for soybean meal in the diet of Mong Cai sows in Centr al Vietnam. (Editor: Reg Preston) International Conference on Livestock, Climate Change and Resource Depletion, Champasack University, Pakse, LAO PDR, 9-11 November 2010 . http://www.mekarn.org/workshops/pakse/html/duyet1.htm

Khieu Borin, Lindberg J E and Ogle R B 2005. Effect of variety and preservation method of cassava leaves on diet digestibility by indigenous and improved pigs. Animal Science 2005, 80: 319-324.

Leterme P, Angela M L, Estrada F, Wolfgang B S and Buldgen A 2005 Chemical composition, nutritive value and voluntary intake of tropical tree forage and cocoyam in pigs. J. Sci. Food Agric. 85: 1725-1732.www.bsas.org.uk/Publications/Animal_Science/2006/Volume_82_Part_2/175/pdf

Manivanh N and Preston T R 2011 Taro (Colocacia esculenta) silage and rice bran as the basal diet for growing pigs; effects on intake, digestibility and N retention. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 23, Article #55. Retrieved December 12, 2011, from http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd23/3/noup23055.htm

Man N V and Wiktorsson H 2002 Effect of molasses on nutritional quality of Cassava and Gliricidia tops silage. Asian Australasian Journal Animal Science, 15, 1294- 1299.

Man N V, Khang D V and Wiktorsson H 2009 Ensiled cassava tops used as a ruminant feed. . In Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT) 2009. Proceeding of International Workshop on “The use of Cassava Roots and Leaves for On Farm Animal Feeding” held in Hue, Vietnam. Jan 17- 19, 2005. . Editor: R. H. Howeler. PP, 152-164.

McDonald P 1981 Biochemistry of Silage. John Wiley & Sons Ltd (July 15, 1981)

MINITAB 2000 Minitab reference Manual release 13.31.

Nguyen Thi Hoa Ly 2006 The use of ensiled cassava leaves for on farm pigs feeding in central Vietnam. n Proceeding of Workshop on Forages for Pigs and Rabbits. Organized and Sponsored by CelAgrid and MEKARN Programme held in Phnom Penh, 21- 24 August 2006.

Nguyen Van Lai, Rodriguez Lylian and Preston T R 1998 Digestion and N metabolism in Mong Cai and Large White pigs having free access to sugar cane juice or ensiled cassava root supplemented with duckweed or ensiled cassava leaves. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 10, No. 2 Article #11.hhttp://www.lrrd.org/lrrd10/2/lai1012.htm

Preston T R 2001 Potential of cassava in integrated farming systems. Proceedings of workshop on "Use of cassava as animal feed", Khon Kaen University, Thailand http://www.mekarn.org/prockk/pres.htm

Preston T R 2006 Forages as protein sources for pigs in the tropics. Proceeding of Workshop-seminar "Forages for Pigs and Rabbits" MEKARN-CelAgrid, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 22-24 August, 2006. http://www.mekarn.org/proprf/preston.htm

Rodríguez L and Preston T R 2009 A note on ensiling the foliage of New Cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium). Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 21, Article #183. http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd21/11/rodr21183.htm

Rodríguez L, Preston T R and Peters K 2009 Studies on the nutritive value for pigs of New Cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium); digestibility and nitrogen balance with different levels of ensiled leaves in a basal diet of sugar cane juice. Livestock Research for Rural Development. Volume 21, Article #27. http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd21/2/rodr21027.htm

Statistical Yearbook 2008. Statistical Publishing House , Hanoi, Vietnam.

Tiep P S, Luc N V, Tuyen T Q, Hung N M and Tu T V 2006 Study on the use of Alocasia macrorrhiza (roots and leaves) in diets for crossbred growing pigs under mountainous village conditions in northern Vietnam. Workshop-seminar “Forages for Pigs and Rabbits” MEKARN-CelAgrid, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 22-24 August, 2006. http://www.mekarn.org/proprf/tiep.htm