|

|

|

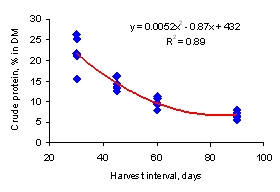

Figure 1. Crude protein content of leaves of Mimosa pigra at different cutting intervals |

Figure 2. Condensed tannin contents of leaves of Mimosa pigra at different cutting intervals |

| Back to content |

Livestock, Climate Change and the Environment |

Mimosa pigra is a shrub legume that is considered to be a dangerous weed impacting crop production in the Mekong Delta. The usual approach to the control of this species is to eliminate it. This is costly and not always effective and can have negative environmental effects if agro-chemicals are used An alternative way is to utilize it as a feed for animals. Studies conducted recently show that Mimosa pigra is an excellent feed for goats. Growth rates of 98 g/day were recorded in goats grazing exclusively on Mimosa. Fed in confinement, in a cut-and-carry system as the sole feed, the growth rates on mimosa alone were a little lower (83 g/day). It is concluded that Mimosa pigra can provide all required nutrients for goats, and that the tannins present in the leaves (about 4% in DM) help to protect the protein from attack by rumen microbes, thus providing a source of protein with rrumen "bypass" characteristics. Thus instead of being an "invasive" weed, Mimosa pigra becomes a valuable feed resource for goats, supporting high growth rates.

Mimosa pigra (Mimosaceae) is native to Central and South America. In Vietnam, the local names of Mimosa pigra are Nguu Ma Vuong and Rinh Nu Nhon. Mimosa pigra is actually a dangerous weed for crop production in the Mekong Delta. It is a serious threat against the lives of many local plants. Mimosa is now found in all 12 provinces of the Mekong Delta, but concentrated mainly in the freshwater zone. Upstream provinces of Long An, An Giang, and Kien Giang are most heavily infested (Tran Triet et al 2007).

Mimosa pigra is controlled by many methods such as : biological control, chemical control (using herbicide), physical and mechanical control, ecological management (use of fire and competitive pastures). However, some of these methods are not good for the environment or a waste of money. For example, green mimosa is difficult to burn and fires generally stop just inside dense infestations unless carried by high-velocity winds. Fire will, however, pass through scattered infestations where there is under-storey fuel. Moreover, the effects of burning are just as complex on mimosa as on other woody species (Miller et al. 1990).

A study to define the biomass and the feed value of Mimosa has been carried out in the block A4 in Tram Chim National Park, in Tam Nong district, Dong Thap province, which is impacted seriously by mimosa invasion. The treatments in a randomized block design were 4 harvest frequencies of 30, 45, 60 and 90 day intervals. The wild mimosa plants were cut to 10 cm above ground level at the start of the trial. The DM yield response to increasing harvest interval was curvilinear reaching a maximum value with a harvest interval of 60 days followed by a steep decline to 90 days .Yield of crude protein as leaves showed a similar trend to DM. The content of crude protein in leaves decreased (Figure 1) while the concentration of condensed tannins increased (Figure 2). Thus, the suitable harvest time to have the best productivity and nutrition is probably at 45 days with 14% crude protein and 4% condensed tannins in the DM of the leaves. . According to Barry (1985), tannins can have a beneficial effects by protecting the protein degraded in the rumen by forming protein-tannin complexes. Some studies demonstrated the crude protein content of mimosa leaflets ranged from 17,9% to 21,21% (in DM) (Table 1). We can see that mimosa is really a protein resource for ruminants.

|

|

|

Figure 1. Crude protein content of leaves of Mimosa pigra at different cutting intervals |

Figure 2. Condensed tannin contents of leaves of Mimosa pigra at different cutting intervals |

|

Table 1 Chemical composition of Mimosa pigra (% of DM, except fopr DM which is on fresh basis) |

||||||

|

The parts of the mimosa |

DM |

CP |

OM |

ADF |

NDF |

References |

|

Leaflets |

36,04 |

20,69 |

92,82 |

37,92 |

53,38 |

Nguyen Thi Thu Hong et al 2005 |

|

Leaflets |

42,02 |

21,21 |

92,82 |

- |

- |

Nguyen Thi Thu Hong et al 2007 |

|

Leaflets |

32,9 |

18,2 |

93,9 |

27,5 |

35,4 |

Nguyen Thi Thu Hong et al 2008 |

|

Leaflets |

37,5 |

17,9 |

91,8 |

- |

- |

Supharoek Nakkitset et al 2008 |

According to Nguyen Thi Mui and Preston (2005), the importance of fodder trees as a source of green forage is based on availability during the time when other feed resources are scarce. Although the protein quality of leaves of trichanthera, gliricidia, leucaena, flemingia was shown to be less than that of traditional protein concentrates, the economic analyses indicate a higher net profit using foliage. This is important to the Vietnamese farmers because of the low availability of cash for investments. For this reason, using new fodder trees as mimosa for ruminants is really necessary.

In an experiment on cooperative farms in Tram Chim National Park in Tam Nong District, Dong Thap Province in the Mekong Delta, sixteen growing goats were allocated to 4 farm households, according to a 2*2 factorial arrangement of four treatments:

G: Grazing of Mimosa pigra

GS: Grazing of mimosa in the day time and supplemented with grass at night

C: Confined, and feeding with 100% Mimosa pigra

CS : Confined, and feeding with Mimosa pigra and grass free choice

The higher growth rates of goats grazing Mimosa compared with being fed the foliage in confinement could be due to increased opportunity for selection of the leaves, and their “freshness”, in the former system.

|

|

Figure 3. Mean values for live weight gain of goats offered Mimosa by grazing or in confinement, and supplemented with para grass or not supplemented |

The excellent growth rates in both experiments with Mimosa as the sole feed

implies that the foliage is providing adequate amounts of both rumen fermentable

and “bypass’ protein. The condensed tannin level of 4 to 5% in the DM of the

“young” Mimosa foliage is the probable reason for the good rumen bypass

characteristics.