Increasing the germination capacity of tree

cuttings

Sorn Suheang

Royal University of Agriculture (RUA),

Chankar Daung, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

suheang@mekarn.org ssuheang@yahoo.com

Abstract

This experiment aimed to evaluate traditional farmer practice of peeling the bark from tree cuttings before planting them. Sixteen cuttings from each tree (Trichanthera gigantea, Hibicus rosa sinensis, Muntingia calabura and Ceiba pentandraw) were used in a 2*4 factorial arrangement. The bark was peeled from the bottom 3 to 4 cm of 8 cuttings of each tree, the other 8 serving as controls. The cuttings were planted in plastic bags containing a mixture of soil and composted organic matter.

Peeling the cuttings of Trichanthera and Hibiscus increased the rate of appearance of green shoots, but appeared to decrease the development of the roots, especially in Trichanthera. This treatment had no effect on cuttings of Ceiba pentandra which produced green shoots soon after planting but almost no roots. Cuttings of Muntingia calabura germinated quickly but they all died within 12 days of planting, therefore vegetative propagation does not seem to be suitable for this tree.

Key words: Bark, germination, Ceiba pentandra, Muntingia calabura, Hibiscus rosa siensis, Trichanthera gigantea, roots, vegetative propagation

Introduction

Fodder from trees and shrubs are an important source of protein for animals in tropical countries (FAO 1992). Trees play other important roles such as controlling erosion, providing sinks for carbon dioxide and methane (at the interface between the decaying fallen leaves and the soil) and as a source of biodiversity. The trees have well enveloped systems of biological pest control, require minimum synthetic chemical inputs and are easily separated into high and low fiber fractions as required for the different end uses of feed for monogastric and ruminant animals and fuel; multipurpose trees also play a critical role in intensive integrated farming systems (Preston and Murgueitio 1992).

The economic significance of trees and shrubs can be determined from the fact that they are hardy and can provide year-round fodder to be used as a supplement in lean periods. With proper management and propagation techniques, this fodder can be a viable feed resource to supplement the income of small and landless farmers. In mixed farming systems, fodder, trees and shrubs can have a stabilizing effect on prices as farmers have a longer holding capacity and are not forced into selling animals in periods of drought. Both trees and shrubs also provide multiple benefits (fuel, wood for furniture and other uses, leaves and shoots for use by animals).

On the other hand, since shortage of animal feed is a big problem for livestock development in the dry season, fodder trees are potentially important to small scale farmers to facilitate use of local available feeds and to increase the efficiency of the production system.

Some trees have had more farmer impact compared to others, and this will depend on the species of animal to be fed. In this connection, foliage from Trichanthera gigantea is readily consumed by pigs; whereas foliages from other trees such as Leucaena leucocephala and Gliricidia sepium are more appropriate for ruminants.

Trichanthera gigantea is a tree of the Acanthaceac family and is apparently native to Andean foothill of Colombia, but it is also found along streams and in swampy areas from Costa Rica to north South America (McDade 1983; Rosales and Gill 1997) and in the wet forest from Central America to Peru and the Amazon basin (Record and Hess 1972). It is a very promising fodder tree for a wide range of ecosystems and is well adapted to the humid tropics with an annual rainfall between 1,000 to 2,800 mm (Acero 1985; Jaramillo and Corredor 1989). It grows well in acid pH and low fertility but well drained soils (Acero 1985). It is not a legume tree but its vigorous regrowth even with repeated cutting and without fertilizer applications indicates that nitrogen fixation occurs in the root zone either through the action of mycorrhiza or other organisms (Preston and Murgueitio 1992). Since its introduction to Vietnam in 1992, it has become very popular with farmers throughout the country (Nguyen Thi Hong Nhan et al 1997).

Muntingia calabura is a tree belonging to the family Elaeocarpacae. It can grow everywhere (sandy land, humid area, high land area) and is well adapted to the dry season.

Hibiscus rosasinensis belongs to the Malvacae family. It is adapted and grows well during the dry season and is used as animal feeds, with emphasis for rabbits and goats (Nguyen Xuan Ba and Le Duc Ngoan 2003).

Ceiba pentandra is a tree belonging to the family of Bombacaceae. It is a medium to large, deciduous tree with tiered, horizontal branches and palmate compound leaves of 5-9 leaflets. The fruits are oblong, smooth and light green in color. While still on the tree, the fruits burst open after the leaves have fallen, exposing the cotton like substance which is the Ceiba pentandra of commerce.

The widespread use of trees as a component of integrating farming systems greatly depends on tree propagation, and in this connection, it is a common practice to use cuttings from trees and shrubs instead of seeds.

The objective of the present communication was to report an experiment undertaken to study two different methods of provoking germination in the four tree species described above. The approach taken was based on farmer practice in Colombia, whereby the lower part of the tree cutting is "peeled" before planting (Photo 1).

Photo 1: Vegetative

propagation of mulberry (Morus alba) trees in Colombia; The cuttings

in the right of the picture were peeled before planting; those on the left

were

not peeled (source: T R Preston, personal communication)

Materials and methods

Location

The study was carried out at An Giang University, Vietnam, from August 1 to 28, 2003.

Treatments and design

There were two factors:

Effect of peeling:

- Peeled (P)

- Not peeled (NP)

Tree species:

- Trichanthera gigantea (TG)

- Muntingia calabura (MC)

- Hibiscus

rosasniensis (HS)

- Ceiba

pentandra (CP)

There were eight replications of each treatments arranged in a spit plot design with the effect of peeling being the sub-plot and the four species the main plots (Table 1).

|

Table1. Layout of the experiment |

||||||||

|

Replication |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

Trichanthera gigantea |

NP |

P |

NP |

P |

P |

NP |

P |

NP |

|

P |

NP |

P |

NP |

NP |

P |

NP |

P |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Muntingia calabura |

P |

NP |

NP |

P |

P |

NP |

P |

P |

|

NP |

P |

P |

NP |

NP |

P |

NP |

NP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hibiscus rosa sinensis |

NP |

P |

P |

NP |

NP |

P |

NP |

NP |

|

P |

NP |

NP |

P |

P |

NP |

P |

P |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ceiba pentandra |

NP |

NP |

P |

NP |

P |

P |

NP |

NP |

|

P |

P |

NP |

P |

NP |

NP |

P |

P |

|

Procedure

Sixteen cuttings

each about 30 cm long were taken from each tree. They were divided into two

groups that were similar in length and diameter. The cuttings in one of the

groups were peeled with a knife, removing the bark from the lower 2 to 3 cm of

the cutting (Photo 2).

Photo 2: Peeled and unpeeled cuttings

Measurements

Records were kept of the day when the first green shoot appeared on the stem. At the start of the experiment the length above the ground of the cutting and the diameter at the mid-point were measured. At the end of 28 days, the cuttings were removed from the bag and the number and of roots was recorded.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by the GLM option of the

Minitab ANOVA software, version 13.31. Sources of variation in the

model were: peeling, species, error.

Results and discussion

The Muntingia cuttings germinated but then all the cuttings died after 12 days. These data were therefore removed from the analysis, which was restricted to Trichanthera, Hibiscus and Ceiba. Both the Trichanthera and the Hibiscus responded to the peeling treatment (Table 2: Figure 1), with a shorter period to appearance of the first green shoot. There was no effect on the Ceiba which was the first to germinate.

|

Table 2: Days to appearance of first green shoot in cuttings of three trees that were peeled or not peeled prior to planting |

||

|

|

Not peeled |

Peeled |

|

Ceiba |

6.63 |

6.50 |

|

Hibiscus |

11.57 |

8.88 |

|

Trichanthera |

13.9 |

10.4 |

|

Mean |

11.4 |

9.74 |

|

SEM/Prob. |

1.18/0.003 |

|

Figure 1: Days to appearance of the

first

that were peeled or not peeled

There was a strong indication (P=0.079) that fewer roots developed on the cuttings that were peeled before planting (Table 2). The tree that was most affected was Trichanthera (Figure 2).

|

Table 2: Numbers of roots (28 days after planting) on cuttings of three trees that were peeled or not peeled prior to planting |

||

|

|

Not peeled |

Peeled |

|

Ceiba |

1.38 |

0.33 |

|

Hibiscus |

6.33 |

3.00 |

|

Trichanthera |

35.4 |

25.4 |

|

Mean |

14.4 |

9.58 |

|

SEM/Prob. |

3.24/0.079 |

|

Figure 2: Numbers of roots on the

cuttings of

that were peeled or not peeled (28 days after planting)

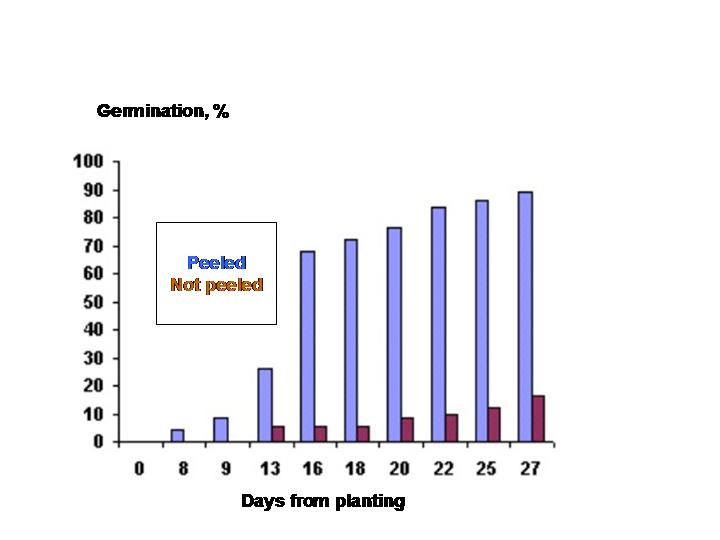

The beneficial effect on germination of peeling the lower point of the cuttings of Trichanthera and Hibiscus prior to planting is in agreement with the findings from Colombia (G Hernandez and T R Preston, personal communication), where the treatment was applied to mulberry (Morus alba) (Figure 3) and Gliricidia sepium. The significance of the apparent reduction in root development is not known, but indicates the need to study the effect of peeling subsequent growth and survival of the trees.

Figure 3: Effect of peeling cuttings of

mulberry on the rate of germination (blue columns are

the peeled cuttings and the red columns are the control)

Conclusions

Peeling the bottom 3 to 4 cm of cuttings of Trichanthera and Hibiscus increased the rate of appearance of green shoots, but appeared to decrease the development of the roots, especially in Trichanthera. This treatment had no effect on cuttings of Ceiba pentandra which produced green shoots soon after planting but almost no roots.

Cuttings of Muntingia calabura germinated quickly but they all

died within 12 days of planting, therefore vegetative propagation does not seem

to be suitable for this tree.

Acknowledgements

The mini-project was carried out at An Giang University, Vietnam. This is a part of the MSc course supported by the regional MEKARN project, financed by sida-SAREC. I would like to express gratitude to Dr Thomas R Preston, Dr Julio Ly and Dr Do van Xe for patient guidance and encouragement and making it possible for me to complete the mini-project. I also would like to express my sincere thanks to staff of UTA, Mr.San Thy and Mr. Chhay Ty and An Giang University staff who provided valuable assistance in preparing materials for conducting the mini-project.

References

Acero L E 1985 Trees from the coffee region of Colombia. Volume 16. 132 pp

FAO 1992 Legume trees and other fodder trees as protein sources for livestock. Animal Production and Health Paper No. 102. FAO, Rome

Jaramillo J H and Corredor G 1989 Plantas forrajeras : proteina barata para el ganado. Revista Federacion Nacional de Cafetaros de Colombia.

Nguyen Thi Hong Nhan, Nguyen vanho, Vovan Son,

PrestonT R and Dolberg F 1996 Effect of shade on

biomass production and composition of the forage tree Trichanthera

gigantea. Livestock Research for Rural Development, Volume 8, and

Number 2:

http:www.cipav.org/lrrd/lrrd11/3/nhaa113.htm

Preston T R and Murgueitio E 1992 Strategies for Sustainable Livestock Production in the Tropics. CONDRIT Ltd; Cali, Colombia pp 90

McDade L A 1983 Pollination intensity and seed set in

Trichanthera gigantea (ACANTHACEAE). Biotropical

15(2):122-124

Nguyen Xuan Ba and Le Duc Ngoan 2003: Evaluation of some unconventional trees/plants as ruminant feeds in Central Vietnam; Livestock Research for Rural Development (15) 6 Retrieved, from http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd15/6/ba156.htm

Nguyen Thi Hong Nhan, Preston T R and Dolberg F 1997 Use of Trichantera gigantea leaf meal and fresh leaves as livestock feed. Livestock Research for Rural Development. (9)1: http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd9/1/nhan91.htm

Rosales M and Gill M 1997 Trichanthera gigantea (Humboldt & Bonplant Nees): A review. Livestock Research for Rural Development (9)4: http://www.cipav.org/lrrd/lrrd9/4/mauro942.htm

Robison P and Thompson I 1989 Fodder trees Nurseries and

their central role in the farming systems of Nepal.